Prabhupada and the “God Is Dead” Controversy

In Die frohliche Wissenschaft (usually translated as The Cheerful Science or The Gay Science), published in 1882, Nietzsche puts the words in the mouth of a fictional character known simply as “the madman.” After entering a busy marketplace, the character asks, “Where is God?” Reacting to his audacity, mobs of people ridicule him, prompting him to respond to his own question:

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. Yet his shadow still looms. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

Thus, Nietzsche’s decree was not a denial of God but a proclamation that the modern world (for him, nineteenth-century Germany) had moved beyond the traditional God of Christianity and the sense of morality that had come from the Bible. When Nietzsche wrote, “God is dead,” he was referring to the plight of modernity, indicating that its people had outgrown contemporary European society, its laws, customs, and religious institutions. But now what? Through the mouth of a madman, Nietzsche questions what we should do now that society has taken God – at least as He was previously understood – out of the equation.

Nietzsche does not mean that God has experienced a physical death (since God is not a physical being). Instead, he hypothesizes that if a Christian society starts to doubt the existence of a spiritual being, the moral fabric of such a society will be pulled apart. Nietzsche is not trying to kill God himself; society had already done that. He is trying to posit a way for humanity to reconstruct itself in the vacuum left by the destruction of Christian morality.

“God Is Dead” Reprise

After Nietzsche’s time, the “God is dead” notion died down – until the 1960s, when it reincarnated by way of an informal group of Protestant theologians, including Thomas Altizer, Gabriel Vahanian, Paul van Buren, William Hamilton, and others. They expressed the need to make God more relevant in the modern world. Preferring Paul Tillich’s conception of the divine as “the ground of Being” (as opposed to a personal deity), and heeding Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s insistence that Christians “come of age,” these theologians wanted to recreate religion from the ground up, beginning with the “death of God” as we know Him. Theirs was an attempt to accommodate secularization and a world enamored more by science than by spirituality. To this end, they made prodigious use of Nietzsche’s phrase.

Their modernist position garnered considerable popularity in the West, reaching a highpoint with Time magazine’s cover story on April 8, 1966: “Is God Dead?” The article addressed possible reasons for America’s growing atheism and the work of the “God is dead” theologians. Just a few months earlier (January 9, 1966), The New York Times had run a similar story that also focused on the new Protestant theology. Nietzsche would have been proud.

But not everyone bought the idea, then or now. For example, theologians such as Karl Barth and John Warwick Montgomery countered “God is dead” theology to good effect. More currently, Michael Shermer’s article “Why Nietzsche and Time Magazine Were Wrong” pokes holes both in Nietzsche’s prediction of increasing secularization and in the philosophical position of the “God is dead” theologians. As evidence, he cites the fact that an ever-increasing number of people in the West are still religious or spiritual, despite the emphasis on science. Additionally, Shermer notes, statistics indicate that few have felt the need to shift their belief to a depersonalized God or to nontraditional forms of religion.

Bringing God Back to Life

In the spring of 1966 – when Time and other news media were rife with “God is dead” coverage – Srila Prabhupada was starting his movement in New York City. Judging by how frequently he used the phrase “God is dead,” he was aware of the relevant news items. His first documented use of the phrase, in fact, occurred in April of 1966, just as national periodicals were first apprising people of this new trend in Christian theology. From then on, it would consistently arise in his public lectures: “In America,” he said, “when I first went, they were popularizing the theory that ‘God is dead.’ But they again accepted and said: God is not dead, but He is here with Swamiji.”

Prabhupada seemed to know about the Protestant dimension, too, or at least that the idea had penetrated the Christian tradition: “At the present moment in many Christian churches, this philosophy is being taught that God is dead. But so far we are concerned, we cannot accept this philosophy, that God is dead. But we preach on the other hand that God is not only not dead, but He can be approached finally face to face. And the method is very simple, chanting the holy name of God.”

Prabhupada’s guru, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, had briefly referred to the “God is dead” theme in his introduction to the Brahma-samhita, written in the 1930s. Since this predates the Time magazine article by several decades, he was likely recalling Nietzsche, but Prabhupada’s usage seems to suggest his awareness of the theme’s more contemporary manifestation.

As for Prabhupada’s books, “God is dead” appears in his Bhagavadgita As It Is, Srimad- Bhagavatam, Beyond Illusion and Doubt, Mukunda Mala Stotra, Quest for Enlightenment, Elevation to Krishna Consciousness, A Second Chance, The Laws of Nature, and several others. It appears most frequently in books generated from lectures and conversations, such as The Science of Self- Realization and The Journey of Self-Discovery, indicating that he found the topic useful when speaking in public. An online search reveals that he used the phrase well over a hundred times in dialogues, lectures, and letters.

Why Was Prabhupada So Concerned?

The phrase “God is dead” encapsulates much of what Prabhupada came to correct in the western world. For example, consider the last sentence uttered by Nietzsche’s madman: “Must we ourselves not become gods . . .?” Prabhupada equates the notion of “God is dead” with the attempt to usurp God’s position. After all, why kill off the Supreme if we don’t want, at least on a subliminal level, to replace Him? Prabhupada says, “So these atheistic theories, that ‘Everyone is God,’ ‘I am God’ ‘You are God,’ ‘God is dead,’ ‘There is no God,’ ‘God is not a person’ – we are fighting against these principles. We say, ‘God is Krishna . The Supreme Personality of Godhead is Krishna . He is a person, and He is not dead.’ This is our preaching. Therefore it is a fight.”

Implied in “God is dead” is this: “If God is dead, then I can do as I please. I answer to no one. I am, in effect, God.”

In Prabhupada’s words:

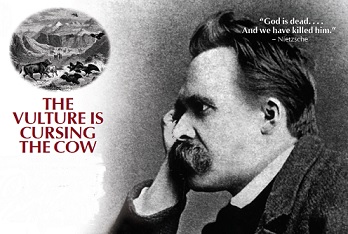

There is a nice Bengali proverb, sakuni svape garu more na. Sakuni means the vulture. The vulture wants some dead carcass of an animal, a cow especially. So for days together it does not get it, so it is cursing some cow. “You die.” So does it mean that by his cursing the cow will die? Similarly, these vultures, sakuni, they want to see God is dead. At least, they take pleasure. “Oh, now God is dead. I can do anything nonsense I like.” This is going on. Sakuni is cursing. The vulture is cursing the cow.

Many of the “God is dead” theologians based their work on the prominent twentieth-century Protestant philosopher Paul Tillich, who famously referred to God as the “ground of Being,” as opposed to a Supreme Person, or as a “God who is above the God of theism.” Thus, he perpetuated the Mayavada doctrine of an impersonal Absolute, albeit in western terms. In fact, the word Brahman, the Sanskrit term for the impersonal Godhead, is often translated as “ground of being,” the phrase popularized by Tillich. Prabhupada came to the West to show the limitations of this impersonalistic conception. For God to be complete, Prabhupada taught, He must have both impersonal and personal features.

This whole cosmic manifestation is nothing but the expansion of the potency or energy of Krishna . This is the conclusion. This expansion of energy is impersonal. Krishna . . . He is the original source. The sunshine is coming from the sun globe, but the sun globe is more important than the sunshine. Similarly, Krishna ’s personality is more important than His impersonal feature, the expansion of His energy. If we understand the example of the sun, then it is very easy to understand the difference between the impersonal and the personal features of the Absolute Truth.

Prabhupada saw the “God is dead” philosophy as a simple lack of intelligence, or at least a lack of the kind of intelligence that allows one to distinguish matter from spirit.

God is not dead; your intelligence is dead. You have a dead body, and you’re proud of it. The body is just like a motorcar. A motorcar is dead, and if there is no driver it does not work. Similarly, the body is dead, and as soon as you, the soul, leave the body, it stops working. That means you are occupying a dead body. It is working only as long as you are there, but actually the body is dead. And you are decorating a dead body. All your acquisitions are simply decorations on a dead body. Apra∫asyaiva dehasya ma∫- ∂anam loka-rañjanam. Some rascal may applaud, “Oh, you are so intelligent; you are decorating your body so nicely.” But an intelligent man will say, “What a fool he is, that he’s decorating a dead body.”

An Inaccurate Conception, To Say the Least

In the Bhagavad-gita (2.27) Krishna declares, “One who has taken his birth is sure to die, and after death one is sure to take birth again. Therefore, in the unavoidable discharge of your duty, you should not lament.” Consequently, the death of God is necessarily an inaccuracy, to say the least, since He never took birth. He says this Himself later in the Gita (7.25): “I am never manifest to the foolish and unintelligent. For them I am covered by My internal potency, and therefore they do not know that I am unborn and infallible.” Of course, proponents of the “God is dead” doctrine do not literally say that God suffers conventional death. But their conception has many other flaws, as Prabhupada has shown in the few examples cited above.

Hari Sauri Dasa, who served as Prabhupada’s secretary and traveled with him extensively in 1975 and 1976, documented how Prabhupada spoke about “God is dead” while in his presence:

In class, Srila Prabhupada continued to preach on points raised during the walk, especially the idea that “God is dead.” . . . Once again Srila Prabhupada’s common sense logic revealed the narrow and limited thinking of atheistic philosophers. “This is our position. . . . God is not dead; God is coming very soon. Wait a few years. . . . You rascal, God is not dead. God is coming to kick you, to kill you. . . . What is death? You have to change your body. It may be lower degree or higher degree, but you have to change your body. There are 8,400,000 species of life, forms of life. You have to accept one of them. That is our real problem. If we forget the real problem and blindly or foolishly say that God is dead – God may be dead – but God’s law is not dead. Suppose a king dies, does it mean the government dies? Hmm? The government will go on. You can say God is dead – God is not dead, neither you are dead – but if you foolishly say that God is dead that does not mean His law is also dead. The law will go on. One king may be dead. The next, his son or somebody will become king and the government law will go on. So what is the use of talking foolishly like God is dead. God is never dead. This is going on. . . .”

Prabhupada declared that anyone who proclaims such a philosophy is actually dead, because he identifies with the gross physical body, which is always dead. It is simply a machine and moves only due to the presence of the soul. As Krishna chastised Arjuna in the beginning of the Bhagavadgita for his bodily concerns, Srila Prabhupada similarly criticized the modern-day thinkers. “So all these rascal philosophers they are writing about this body. That’s all. But this is not the subject matter for the learned scholars. What is this body? A combination of matter. It is moving and as soon as the living soul is out of the body it is useless. So what is the importance of talking about this dead body?”

His conclusion was as crushingly final to the foolish philosopher’s speculative talk as death itself. “When death will come no one will save you. You are challenging God is dead. When God will come and make you killed, nobody can save you. We are so foolish for thinking that God is dead and I shall continue my life and my wife, my children, my countrymen, my nation will save me. That is not possible.”

In his “God is dead” philosophy, Nietzsche was reacting to the rulebound Christianity of his rigid era, as were the Protestant theologians of the 1960s. But they went too far. Prabhupada came to set the record straight through a devotional process of chanting and dancing. Nietzsche, in fact, would have appreciated Prabhupada’s process, for it is said that the German philosopher showed his appreciation of the sacred through dance. Indeed, Nietzsche danced daily, saying it was his “only kind of piety,” his “divine service.” To conclude, then, I’ll invoke one of Nietzsche’s most famous sayings: “I should only believe in a God who knows how to dance.”

Satyaraja Dasa, a disciple of Srila Prabhupada, is a BTG associate editor and founding editor of the Journal of Vaishnava Studies. He has written more than thirty books on Krishna consciousness and lives near New York City.