The 170 million motor vehicles registered in the United States pump 80 million tons of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, and hydrocarbons into the air annually. Auto exhaust accounts for most of the smog that hangs over U.S. cities, and that smog is a major cause of emphysema, bronchitis, lung cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and asthma. By rough calculation, breathing the air in New York City is as likely to cause lung cancer as smoking two packs of cigarettes a day.

Eighty years ago, when the automotive industry was just getting under way, no one foresaw that motor vehicles would cause so much pollution. On the contrary, early enthusiasts hailed the auto as a remedy for pollution and other urban maladies. At the turn of the century, horse-drawn carts and carriages with steel-rimmed wheels clattered along the cobblestone streets, creating a sometimes intolerable din. Horse manure littered city streets, and the resulting fumes irritated nasal passages and lungs. Dried horse dung gave rise to a kind of dust that medical authorities blamed for the dysentery and diarrhea plaguing city children. Tetanus was thought to be introduced into the cities in horse fodder, and thirty communicable diseases, including typhoid, were linked to horses and horse excreta.

Automobiles, many argued, would eliminate the horses, horse manure, smelly and unsightly stables, as well as the cobblestone streets that provided the necessary footing and traction for horses. As a Scientific American article explained in 1899: "The improvement in city conditions by the general adoption of the motorcar can hardly be overestimated. Streets clean, dustless and odorless, with light rubber tired vehicles moving noiselessly over their smoothe expanse, would eliminate a greater part of the nervousness, distraction, and strain of modern metropolitan life."

Not only would automobiles reduce urban stress, but they would create an alternative to urban living. The auto would enable workers to spend the day at their factories and offices in the city and live in the countryside miles away. "Imagine a healthier race of workingmen," the Dearborn Independent exhorted its readers in 1904, "who, in the late afternoon, glide away in their own comfortable vehicles to their little farms or houses in the country. . . . " As Henry Ford put it, "We shall solve the city problem by leaving the city."

The growth of the auto industry did spark a suburban real estate boom, as well as rapid growth in the steel, rubber, plate glass, and other related industries. Between 1910 and 1927, 15 million Model T's rolled off the Ford Motor Company's assembly lines, and the nation laid down hundreds of thousands of miles of paved streets and highways. Both directly and indirectly, the automotive industry contributed greatly to the prosperity of the twenties.

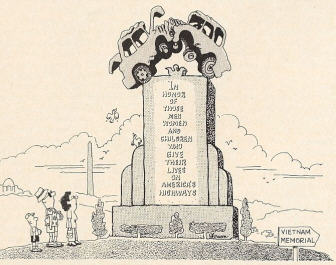

From the start, however, the disadvantages of motor transport were apparent. By the early 1920s, auto traffic in American cities was one of the major problems of the day. And in 1924 alone, 23,600 people, including 10,000 children, died in auto accidents. The number of deaths rose each year to 40,000 by 1940 and to 50,000 by 1965. Since 1965, despite the enforcement of Federal auto safety standards, the figure has remained around 50,000 a year. All told, more Americans have died in motor vehicle accidents than in all the wars America has fought.

In terms of the economy as well, the benefits of the auto industry are questionable. Auto production contributed significantly to the wealth of the Roaring Twenties, but when the market became glutted around 1926, production fell off. This, of course, affected the national economy, and some economists point to the leveling of the auto market in the late twenties as a major factor in the stock market crash of 1929.

Today motor transportation is so intricately woven into the fabric of our life that it's hard to imagine doing without it. The auto not only allows us to live miles from our places of work, our schools, our shopping centers, and our recreational facilities itforces us to. People can no longer spend their days near home and family. The automotive industry has disrupted and divided our lives and made us dependent on our expensive, dangerous, smog-belching vehicles. We spend an enormous amount of time and money to purchase and maintain our cars, and they, in turn, exert an enormous influence on our lives. So the question might be raised: "Who's driving whom?"

And yet, dependent as we are on our automobiles, we may have to do without them, at least to some extent. Motor vehicles in the United States guzzled almost 115 billion gallons of gasoline in 1980, and many authorities fear that at that rate, the supply can't last long.

But would the loss of the automobile be a blow to progress, or would it be a blessing? The Srimad-Bhagavatam points out that although what we so often refer to as progress developing a "higher standard of living" may raise some standards, it lowers others. And the bad effects of such "progress" cancel the good effects. The higher speed of automobiles over horse-drawn vehicles, for example, has brought with it a disproportionate lowering of safety and health standards.

Progress toward material happiness, the Srimad-Bhagavatam states, is always illusory. Endeavors for such progress "result only in a loss of time and energy, with no actual profit." (Bhag. 7.6.4) And that's no exaggeration. Try subtracting the millions killed and maimed in auto accidents from the billions of dollars the auto industry has added to the gross national product. At best, you get zero.

Not only is material advancement unprofitable, but "the results one obtains are inevitably the opposite of those one desires." (Bhag. 7.7.41) For example, such a formidable health menace as air pollution from auto exhaust is the result of attempts to improve public health and the urban environment. And if we think we can escape from auto exhaust by adopting, say, electric cars, or solar cars, we will find other disadvantages to contend with. That's the nature of material progress.

In addition to being self-defeating, material progress diverts our attention from spiritual progress. The Vedas recommend, therefore, that instead of wasting time pursuing illusory material progress, people should live simply and peacefully, devoting their time, energy, and creative intelligence to the service of the Supreme Person, Krsna, and thus free themselves from the cycle of birth and death. Until we are free from the miseries of repeated birth and death, there is no question of a higher standard of living.

A devotee of Krsna will admit that, as things stand now, the automobile is a practical necessity, and he'll use the automobile to take Krsna consciousness to every city and town. But he doesn't mistakenly see the auto as a symbol of progress. He sees that when you tally up all the automotive industry's balance sheets, you find an extremely poor business record: eighty years of hard work and no profit.