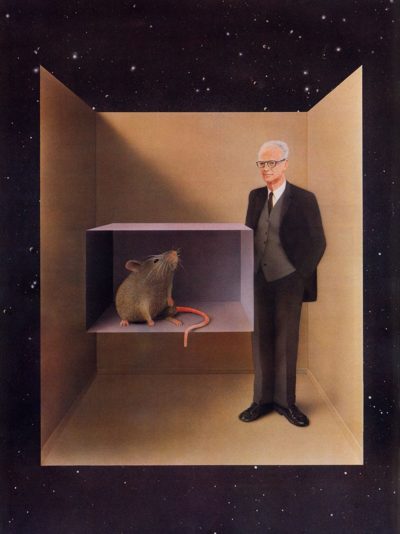

Are we free? Or are we like the behavioural psychologist

B. F. Skinner's rats simply products of our environmental cages?

"Psyche," from the Greek word for soul, connotes an inner spirit as distinguished from its vehicle, the material body. In Greek mythology, Psyche, a personification of the soul, falls in love with Eros, the god of love. Eros later deserts her, and Psyche, brokenhearted roams the world in search of him, performing difficult tasks until at last she becomes an immortal and rejoins him.

I was not acquainted with Psyche's story when I chose, as a college freshman, to major in psychology, her namesake science, but if I had been, her plight would have touched me and spirited my studies. Like Psyche, I had a romantic desire to roam the world searching for, in my case, something I felt was missing in my own self and in the self of all human beings, something that would make me whole and fill mankind with peace and love. Like Psyche, I was ready to work hard, patiently submitting to earthly trials to achieve my goal.

In fact, I had submitted to plenty of earthly trials already. I had, for instance, lived at home with my mother and teenage sister, while my father was usually away on business. My brother was in the Marines in Vietnam. My best friend, a twelve year-old beagle, was gray and arthritic. These and countless other hardships had, I sensed, nurtured in me a natural intuitive genius, as yet untapped, for things psychological. Having paid my dues, I felt ripe for union with my missing inner self. Sort of like Psyche. Too bad we hadn't met.

In my first semester, girded with intuition and away from home at last, I leafed through my course catalog and found a course description that went something like this: "B. F. Skinner and Behaviorism … for sophomores and other students who have completed their introductory studies in psychology and who want to begin a scientific analysis of behaviour."

Perfect. Whoever this B. F. Skinner was, my life experiences, I reasoned, would more than suffice for "introductory studies." And what to speak of sophomores, I was prepared to rub shoulders with the very best.

But B. F. Skinner, it so happened, though the very best in his field of behavioural psychology, was not, and still isn't, a beautiful maiden. Nor does his research into patterns of behaviour much resemble Psyche's search for her lover or my quest for an inner self. Skinner doesn't believe in an inner self, in a psyche as the Greeks conceived it. Skinner and other behaviourists say that the inner self and the mind, if they exist at all, are things we cannot study or measure scientifically. Only our behaviour is plainly visible. "The picture which emerges from a scientific analysis," Skinner contends, "is not of a body with a person inside, but of a body which is a person in the sense that it displays a complex repertoire of behaviour."

Skinner is famous for his experiments with caged animals. His cage, known now as a Skinner box, was equipped with a mechanism that automatically gave the animal food, water, or some other reward. A rat, for instance, might find himself in a cage with a lever and a dish, and when he pressed the lever a food pellet would fall into the dish. Using variations on this simple arrangement, Skinner was able to show how patterns of rewards and punishments control an organism's behaviour.

Skinner's idea, in short, is that we are products of our environment and consequently not responsible for our actions. We are not to blame for our failures, nor do we deserve credit for our achievements. All is done by the environment. In Beyond Freedom and Dignity, his best-known work, Skinner argues that we possess neither freedom nor dignity in the ordinary sense of those words.

This is not what I wanted to hear. If the Skinner box was an experimental model of the world as Skinner perceived it, then in Skinner's eyes, I figured, I was little better than a rat, responding predictably to food, water, and other stimuli. What irked me further was that although we were all supposedly products of our environmental cages, Skinner and other "social engineers," as he called them, could step outside their cages to study and manipulate the rest of us. I hadn't the least desire to join the ranks of the Skinnerian engineers, and besides, with my intuition flagging, I was nearly flunking the course.

Twenty years later I still disagree with much of the Skinnerian creed, but I can more easily admit that I have never been wholly free. I have my own family now, and the crying or laughter of my children, my wife's moods, the arrival of bills or checks in my mailbox, and a host of other stimuli, cause me to behave in quite predictable ways. Even if I wanted to break away, disappearing over the hill and into oblivion, wouldn't that only make me the servant of a different passion? Skinner quotes Voltaire: "When I can do what I want to do, there is my liberty, . . . but I can't help wanting what I do want."

So do I have any freedom? Or am I boxed?

In the Third Chapter of the Bhagavad-gita, Lord Krsna confirms that the environment, or nature, controls behaviour: "The spirit soul bewildered by the influence of false ego thinks himself the doer of activities that are in actuality carried out by the three modes of material nature." Nature is so fully in control, in other words, that we could say that nature, not ourselves, behaves. When "nature," or the environment, is a Skinner box, we might therefore say that the box and its controller, B. F. Skinner, are acting, not the rat, although we would have to take into account that all three the box, the rat, and Skinner are under the influence of a larger controlling environment.

Unlike Skinner, however, Lord Krsna makes a clear distinction between the body and the self, or the person, and between the mind, which is a subtle body, and the person. A human being, He asserts, is indeed a body with a person inside, and that person, or soul, is an eternal individual, an individual who exists both before and after the body's existence.

For the soul there is neither birth nor death at any time…. He is unborn, eternal, ever existing, and primeval. He is not slain when the body is slain. (Bhagavad-gita 2.20)

How do we perceive the soul? By consciousness. The consciousness that pervades our body is the soul's energy, just as sunlight is the energy of the sun.

That which pervades the entire body you should know to be indestructible. No one is able to destroy that imperishable soul. (Bhagavad-gita 2.17)

The material body and mind are temporary clothing for the eternal self, which does not mix with matter, just as oil and water do not mix. What nature controls is the gross body and subtle mind, since they are, after all, part of nature. Nature does not control our eternal self, which is part of Krsna's spiritual energy. But because we are bewildered, we, the eternal selves, identify with the material body and mind, thinking that when the body and mind act, we are acting. This is called false ego. Real ego is to think "I am an eternal person and a part of Krsna." False ego is to think "I am this material body and mind."

Just as a reflection of the sun on a pool of water moves with the movements of the pool, so the soul whose consciousness is fixed on matter appears to move with matter. The fact is, however, that the soul is aloof and as long as it identifies with matter inert.

But we are not forever bound to inertia and false ego. As Skinner is the creator and controller of his boxes, Krsna is the creator and controller of nature. "The material world is working under My direction," He says in the Ninth Chapter of the Gita. The universe, therefore, is a Krsna box, and Lord Krsna has kindly described how His box works and how to free ourselves from the false ego that renders us inert under the spell of material nature.

Krsna explains that nature acts in three modes: goodness, passion, and ignorance. These modes force upon the soul a variety of insurmountable desires to enjoy and control nature. The mode of goodness is characterized by the development of knowledge, and by austerity, steady determination, and sense control. The mode of passion is characterized by the attraction between man and woman, by intense longings for sense enjoyment, and by hard work to acquire material wealth. The mode of ignorance, which Krsna calls "the delusion of all embodied living beings," is characterized by sleep, indolence, madness, and intoxication.

These three modes of nature compete for supremacy over our consciousness, and one mode or another is usually prominent in an individual's behaviour throughout life, although all three are always present. In the mode of goodness there is always at least a tinge of passion and ignorance. And even in the darkest ignorance, which is the predominant mode of the lower animals, there exists a degree of passion and goodness.

The modes direct us to various kinds of enjoyment in the material world, but none of them can bring us to a full understanding of our eternal self or a full realization of the Supreme Personality of Godhead. Rather, the modes distract us from selfrealization. This is because the modes are material while our selves and the supreme self are pure spirit situated in the spiritual mode of pure goodness. Pure goodness is transcendental, untouched and untouchable by the three material modes.

While the material nature is composed of three modes, the spiritual nature is composed entirely of unalloyed goodness. But the Vedic literature informs us that both natures are in fact one nature, one energy of Krsna acting in different ways. When we want to forget Krsna, His nature acts in three modes, both to assist us in that forgetfulness and to punish us with repeated birth and death, thus bringing us to our senses. When we want to remember Krsna, however, the same nature acts to encourage and assist us in the activities of pure goodness.

Activity in the mode of pure goodness is called bhakti, or devotional service to the Supreme Person. Bhakti is both means and end. As the means, the practice of bhakti cleanses us of false ego and revives our pure consciousness that we are eternal servants of Krsna. As the end, bhakti is the eternal activity of the liberated souls who are absorbed in love of God and have no other desire than to serve Him.

The assistance rendered to us by the spiritual nature is nothing like the activities of the three modes, which force us to act contrary to our eternal constitutional identity as pure spiritual individuals. Because the three material modes are presently forcing us to serve material desires, we get a bad experience of servitude. We feel boxed. But service to Krsna in the spiritual world, assisted by the spiritual nature, is not forced service, because there we serve out of spontaneous love, and because there we are in full harmony with nature, which is as fully conscious and fully devoted to the Lord as we are.

So am I free? Or am I boxed?

I am free to choose to associate with the three modes of material nature or with the spiritual mode of pure goodness. Within the three modes, I also have some freedom to choose the mode I prefer. I can, by practice, develop in my life the mode of goodness, the mode of passion, or the mode of ignorance.

The Bhagavad-gita describes the different kinds of work, knowledge, determination, happiness, food, charity, faith, and so on characteristic of each mode. So we have some freedom, in other words, to choose which mode will dictate our desires. And if we like, we can take credit for our successes in fulfilling those dictated desires. But in any case, if I choose to maintain my false ego, I must serve the modes within the cycle of birth and death.

I may also, however, choose to develop the mode of pure goodness through the practice of bhakti in the association of pure devotees of Krsna. If I thus choose to revive my original Krsna consciousness, then I gradually regain my pure status as an eternal servant of Krsna, free to render Him varieties of devotional service with the full cooperation of His deathless spiritual nature.