On April 19 a terrorist explosion destroyed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, taking the lives of 168 people, injuring hundreds more. Many people were surprised to learn that the deadly blast was caused not by some high-security military explosive but by ordinary agricultural fertilizer mixed with fuel oil. How could a peaceful substance like crop fertilizer be used for such an insane and deadly purpose?

But when I heard about the ingredients used, my mind flashed to a passage from An Agricultural Testament, written in 1940 by Sir Albert Howard, the grandfather of modern organic farming:

The feature of the manuring of the West is the use of artificial manures. The factories engaged during the Great War in the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen for the manufacture of explosives had to find other markets. The use of nitrogenous fertilizers in agriculture increased, until today the majority of farmers and market gardeners base their manurial programme on the cheapest forms of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) on the market. What may be conveniently described as the NPK mentality dominates farming alike in the experimental stations and the countryside. Vested interests, entrenched in time of national emergency, have gained a stranglehold. (p. 18)

In other words, artificial nitrogen-based fertilizer is simply a by-product of the military technology of World War I. When the war ended, manufacturers had to find another market for nitrates, so they began to promote artificial fertilizer with phenomenal success. Therefore when the federal office building was blown up a few months ago, the tragic fact is that the chemicals were only doing what they were originally designed to do destroy things, and people.

It occurred to me that the devastation of the Alfred Murrah Building was only the most dramatic example of destruction by chemical fertilizer in the last fifty years. Conservationists like Sir Albert Howard have for decades lamented for soil destroyed when structure-building animal manure is replaced with powdery nitrates. Others have lamented the thousands or millions of small-farm families around the world who have been driven off the land by agribusinesses using tractors and chemical fertilizers.

I began to think how in many ways the recent history of agriculture is simply a by-product of military technology and military policy. Srila Prabhupada states, "God's gifted professions for mankind are agriculture and cow protection." (Light of the Bhagavata) That's because simple living and high thinking provide the ideal environment for spiritual advancement. But the agriculture military technology has given us is not the kind the Lord originally intended. The agrarian by-products of military history lead not to peace and spiritual advancement but to conflict and spiritual backwardness. Let me show you what I mean.

When the last war horses trudged back from the Crusades in the Middle Ages, they and their descendants were put to work in the fields. These powerful horses, bred to carry armored knights into combat, were much faster than oxen. That meant one man could plow more than twice as much acreage as before. It also meant that the ox was sent to the slaughterhouse and that many farmers were driven off their farms to the miserable towns.

Several centuries later, Eli Whitney, known for his invention of the cotton gin, with its staggering sociological and environmental effects, affected agriculture just as much by his role in founding the military-industrial complex. In 1801 he produced 10,000 muskets with interchangeable parts. Comments one author, "His startling concept of interchangeable parts also transformed American industry and launched the Machine Age."

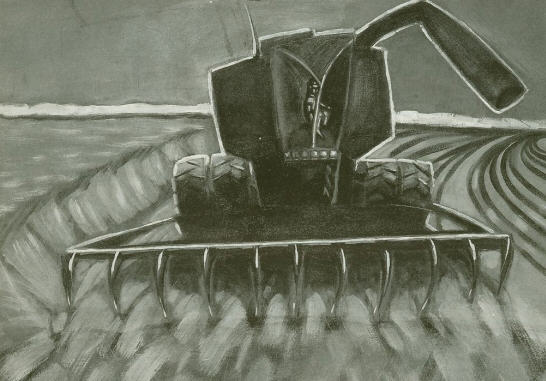

The invention of mass-produced machines with interchangeable parts helped bring on the twentieth-century mechanization of agriculture. That gave us the tractor and combine harvester to produce food crops, and the truck, train, and steam-powered ocean vessels to transport them. By increasing productivity and marketing power for the wealthiest farmers, these technologies helped drive smaller farmers off the land to the cities to a life less favorable for cultivating spiritual values.

A decade after Whitney's mass-produced rifles, Napoleon Bonaparte, facing food shortages caused by the British naval blockade, offered a prize for a way to preserve food. Nicholas Appert won the prize with his technique of sealing boiled vegetables in jars to prevent spoilage. The invention of canning eventually gave rise to large-scale vegetable farming geared for shipping food to long-distance markets rather than growing it for the local community. As crop prices fell, more farms folded; more people went to the city.

Whitney wasn't the only arms producer whose technology would later be used for farm machinery. In 1774 John Wilkinson invented a special lathe to create a uniform bore for cannons. That meant that James Watt finally had someone to produce the piston cylinders for the new steam engine he had designed.

Seventy years later, during the Crimean War, Henry Bessemer invented a method of rotating projectiles that required a superior quality of cast iron to produce guns strong enough to fire his new invention. His next invention was the Bessemer method of converting iron into steel by a process that began to make steel cheap enough for a much wider range of products. Finally, in 1913, on the eve of World War I, Harry Brearley accidentally discovered stainless steel while trying to create a high-chromium steel for rifle barrels.

All these advances in arms production ultimately aided the production of large-scale mechanized farm equipment. The heavy demand for steel for military needs in World War I and World War II sped up factory efficiency, bringing prices for mechanized farm equipment within the reach of farmers just barely.

As early as the late 1800's, paying for all this war-generated technology began to whittle away the farmer's independence. As Robert West Howard explains in The Vanishing Land (p. 85), "The middlemen's usurpation of agricultural markets via the tin can, centralized processing, and shrill salesmanship about the great advantages of iron and steel farm machines eventually crippled the farmer's self-sufficiency and made him as dependent on money as the workers in city sweatshops and tenements. Town and village banks burrowed greedily into agricultural life."

All this took place despite warnings from American farm publications: "A farmer should shun the doors of a bank as he would the plague or cholera. Banks are for traders and men of speculation, and theirs is a business with which farmers should have little to do!"

But by the first World War, thousands of farmers were induced to sell their work animals for the war and gamble their land at the bank:

Artillery and commissary needs sent more than 1.5 million horses and mules overseas, at farm prices of $200 per head and up. The "silk-shirt" years" saw land prices in the Midwest soar to $400, then $500, and finally $600 an acre. Banks and wildcat loan firms worked overtime on applications for "enough money to buy one of those tractors." (Howard, p. 160)

For thousands, the wartime gamble failed to pay off. In October 1929 the stock markets crashed, and over the next 10 years more than 750,000 American farmers lost their land. The auctions of foreclosed farms set off riots and gunfire. Again, thousands of farmers set out to seek non-existent jobs in the cities.

Apparently the only thing that could cure the Great Depression was another war with more repercussions for farmers:

The USDA resurrected the World War I slogan of "Food will win the war"… As in the last war, millions of marginal acres were ripped open and planted to grains or cotton. New irrigation ditches gurgled the reserve water out of reservoirs and aquifers. [Swiss chemist Paul Muller discovered DDT at the beginning of World War II.] Purchase of chemical fertilizers and insecticides doubled and tripled. … Rising prices for harvests persuaded most farmers and ranchers to complete the mechanization of their holdings. (Howard, p. 170)

Thus, by the end of the war only fifteen percent of the population worked on farms. "Farm sizes grew to 400, 800, 1,000 acres, and were dependent on specialty crops and the quantity of machines." War shot down the farmer and replaced his simple agrarian values with urban consumerism. By 1994 only one percent of Americans worked as farmers.

Recent wars have brought more so-called advances for farmers. The Agent Orange defoliant of the Vietnam War has been transformed into Roundup, a popular weed killer.

The conclusion is obvious: When chemical fertilizer blows up a building it's front-page news, but though newspapers take little notice, war-grown agritech kills people and cripples societies around the world, every year. It's just harder to see.

That's why on our Hare Krsna farms we want to get away from the agriculture that's a by-product of military history. We want an agriculture that's a by-product of loving Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead. We want to depend on the cow and the bull and the land rather than on tractors and weed killers and chemical fertilizers. Only a reformed way of living with the land will bring society peace and prosperity.

It's not that Hare Krsna devotees are fanatically against all the by-products of military technology that have come into farming. Most of us eat grains produced with machines rather than with oxen. But our goal is to live as Krsna lived in His farming village of Vrndavana. And in general we see that the highly proclaimed agricultural advances brought to us by war do not bring a peaceful, satisfying life conducive to spiritual understanding. We want to set up a simpler, more natural way to farm that will help us make spiritual advancement.

So, no chemical fertilizers for us, thanks. We don't want the disastrous side effects. We want to use the fertilizer Krsna has given us cow manure. As Srila Prabhupada wrote in a letter to Rupanuga Dasa in January 1976, "We shall never use this artificial fertilizer on our farms. It is forbidden in the sastras [Vedic scriptures]."

It's not that we fear that sprinkling a little nitrate powder on our tomatoes will send us to hell. But if we content ourselves with the sprays and machines handed down to us from the military-industrial complex, we risk shutting ourselves of from the satisfying culture of simple Krsna conscious farming villages. We want the kind of environment where we can see Lord Krsna, the original cowherd boy, face to face. For that we want Krsna's agriculture, not the agriculture of war.

Hare Krsna Devi Dasi, an ISKCON devotee since 1978, is co-editor of the newsletter Hare Krsna Rural Life.