Drug-hallucinations, free sex, undercover CIA activities is

that what you find inside the Hare Krishna movement?

When Dev Anand’s film Hare Rama Hare Krishna first hit the big screen in 1971, few could have guessed the movie’s significance. After all, an industry that churns out thousands upon thousands of movies can hardly expect all of them to have a lasting impact on the history of Indian cinema. And yet this is precisely what Hare Rama Hare Krishna did. The film launched all those associated with it into superstardom. And the soundtrack with the infectiously popular song “Dum Maro Dum” as a centerpiece redefined Indian filmi music forever.

In fact, four decades after Hare Rama, Hare Krishna was first released, the film continues to make waves. A new film, titled Dum Maro Dum after the popular song, hopes to win over new legions of fans with its groovy beats and smoky sensuality. The 2011 film stars some of Bollywood’s hottest A-list celebrities, and features a remixed version of the classic song.

As we mark the 40th anniversary of this historic film, might not there be a darker legacy to consider? Along with the entertaining acting and catchy music, Hare Rama Hare Krishna also seemed to include a strong message about the interaction between India’s spirituality and Western hippies. In his narration to the film’s opening, Anand makes this message clear. He begins by praising “India’s great saintly teachers who crossed the ocean” to bring the holy name of Krsna to distant lands an obvious reference to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, who founded the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), known popularly as the Hare Krishna movement. As footage of real ISKCON devotees chanting and dancing plays on the screen, Anand’s voiceover appreciates how the mantra was spread all over the world. However after a few moments, the scene changes and we see a den of (fictional) hippies, with young people shamelessly taking drugs and dancing seductively. Dev Anand’s narration describes these people as those who chant the names of Krsna and Rama, but are actually “devotees of heroin, marijuana, cocaine, and other drugs.”

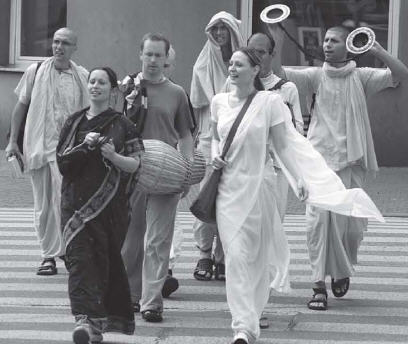

To his credit, Anand’s monologue never explicitly equated the actual devotees with those hippies who “misuse the mantra without properly understanding its significance.” But for many Indian viewers, the connection was made anyway. They walked out of theaters concluding that the white-skinned young men and women they saw chanting Hare Krsna and chiming cymbals were drug-crazed hippies out to exploit Hinduism. Some even began to see the Western devotees as a threat a bad influence out to corrupt Indians in the name of their own religion. Not surprisingly, some conservative Indians kept their distance from these American and European converts and eyed them with suspicion.

But was this a fair assessment of the Hare Krsna movement, or an undeserved stereotype? Was Hare Rama Hare Krishna more fact or fiction?

THE SONG

Taken at face value, the story of Hare Rama Hare Krishna is typically full of twists and turns that characterize a Bollywood movie.

However, the film’s most memorable scene is the one that features the song destined to become a classic “Dum Maro Dum.” It shows hippies gathered together in a celebration of debauchery, drinking alcohol and passing around a pipe filled with hashish, from which they share puffs. Some embrace lustily, while others simply lie on the ground in a drugged stupor. And all the while, the song plays their anthem: dum maro dum, mita jaaye gham bolo subah shaam, Hare Krishna Hare Ram “Take another puff, let your sorrows fade away, and morning and evening chant Hare Krsna and Hare Rama.”

CULTURE CLASH

To understand why Hare Rama Hare Krishna struck such a chord, we need to look at the social landscape of the 1960s and 1970s. All over the Western world, a counter-cultural revolution was underway. Young people many from educated and affluent backgrounds were rebelling against the conservative restrictions, materialism, and hypocrisy of their parents’ generation. Dubbed “hippies” by the mainstream media, some took shelter of mind-altering drugs and a vagabond lifestyle. Others, however, turned to spirituality especially Eastern practices such as meditation, vegetarianism, and accepting a guru. Many felt drawn to India, and soon young Western men and women wearing backpacks and flowers in their hair became a common sight in major Indian cities and towns.

Meanwhile, India was undergoing its own cultural revolution of sorts. The country was modernizing at breakneck speed, and with technological and industrial advances came more and more Westernization. Western fashion, music, and films became increasingly popular. More young Indian men and women began traveling to America and Europe than ever before, either to study or to settle down. As exciting as this new exposure to the West was, however, it also became a source of fear. The West was still regarded as a vastly unknown and powerful force that could overwhelm and even destroy Indian culture. Not surprisingly, the more conservative older generation saw Westernization as a threat. By contrast, like their American and European counterparts, many liberal Indian youth embraced it, seeing it as an opportunity to free themselves from the strictures and limitations of the past.

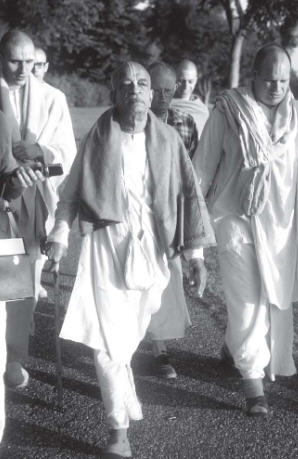

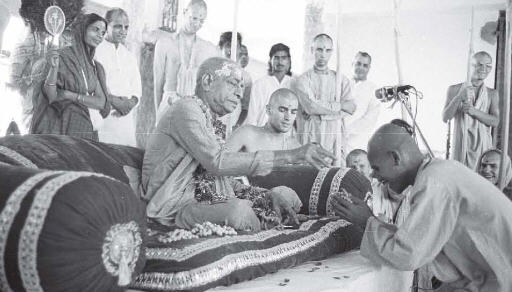

In this context, Srila Prabhupada set sail from India to New York. Although he was alone, with few material resources and practically no contacts in America, Srila Prabhupada’s purity and sincerity soon attracted a following. American men and women came forward to become serious students and eventually initiated disciples. Convinced of Prabhupada’s teachings and transformed by his personal example, many of them moved into ashrams and became full-time devotees. They donned dhotis and saris, learned to play traditional instruments and cook succulent Indian feasts, and began to live according to the strict principles of orthodox Vaishnavas. Above all else, they became dedicated to the chanting of Lord Krsna’s name and sharing their faith with others. The movement began to spread rapidly.

News of this began to trickle back to India, and by the time Srila Prabhupada returned to India with a group of American and European disciples for a homecoming tour, it had become a full-blown sensation. Leading Indian newspapers covered the Western devotees’ arrival as front-page news. When they would chant on the streets, traffic would grind to a halt as the local population simply stood and stared. In some places such as Surat, Gujarat the devotees were greeted with flower petals by the citizens and garlanded by no less than the city’s mayor. Most Indians seemed to have an overwhelmingly positive reaction to the “white-skinned bhaktas.” They felt immense pride to see people of the West take up their faith and traditions with such seriousness.

However, the devotees also had their critics. Some dismissed the non-Indian devotees as sentimental faddists. Others raised objections based on caste; they argued that those born in non-Indian families were untouchables who could never be accepted as “real” Hindus. Still others accused the devotees of having ulterior, even sinister, motives. A handful of these people even came up with a conspiracy theory that the devotees were actually CIA agents in disguise, spying on India to further the interest of America-supported Pakistan.

Whatever their particular objections, critics found their battle cry in the Hare Rama, Hare Krishna film. Now, they could simply point to the film and imply that non-Indian devotees were synonymous with drug-taking hippies. Never mind the fact that the film made no substantial connection between the devotees and the hippies; the mere fact that the chanting of the Hare Krsna maha-mantra and drug-taking were uttered in the same sentence became a kind of “guilt by association.” Now critics could simply dismiss the entire Hare Krishna movement by invoking three simple words “Dum Maro Dum.”

FACT OR FICTION?

But does Hare Rama Hare Krishna measure up to the reality of the Hare Krishna movement in the 1970s? A side-by-side comparison reveals that not only does the film fail to accurately depict devotees almost on every point, it actually conveys the exact opposite.

1. In the film: The female lead character exchanges her Indian values for a Westernized hedonistic lifestyle. She trades in her traditional desi clothes for a miniskirt, and renames herself with a western name.

In reality: The Western-born devotees happily accepted the values of India’s glorious spiritual heritage, and adopted a traditional Vedic lifestyle that even modern-day Indians could hardly maintain. From eating only satvika vegetarian food, to waking up early in the morning and bathing, to dressing in saris and dhotis in every way, these devotees upheld, not degraded, Indian culture. In fact, they even accepted new Sanskrit names, such as Visnu Dasa or Radha Dasi, signifying their new identities as the menial servants of Krsna and His devotees.

2. In the film: The hippies indulge in intoxicants and engage in amorous relationships without restraint. Their lives revolve around the principle of gratifying the senses without restriction.

In reality: The devotees took strict vows of no intoxication including not only hard drugs, but also alcohol, cigarettes, and even coffee, tea, or betel nut (pan). They lived chastely; men and women cooperated for the purpose of serving Krishna together, but did not socialize frivolously or keep girlfriends or boyfriends. A devotee man addressed all devotee women other than his wife as mataji, or “respected mother.” Many devotees lived as celibate monks (brahmachari or sannyasi) or nuns (brahmacharini); even those who were married (grihastha) maintained the highest standards of chastity and personal morality. Their lives revolved around the principle of self-realization and service to Krishna and others.

3. In the film: The hippies sing “Dum Maro Dum” and smoke hashish and then chant the Hare Krishna mantra. When Dev Anand sees this, he cannot tolerate it and follows up with a song of his own entitled “Ram Ka Naam Badnaam Naa Karo” (translation:

“Don’t dishonor the holy name of Lord Rama”) in which he preaches to them to not take the names of Krishna and Rama in vain, but rather to learn the Lord’s teachings and purify their lives.

In reality: Hare Krishna devotees absolutely condemned mixing intoxication and chanting as cheating in the name of religion. They even felt that talking about drug use and chanting in the same sentence was improper and offensive. In fact, ironically, this is exactly why so many devotees of the time were offended by the Hare Rama Hare Krishna movie itself they felt that by indirectly associating the Holy Names with imagery of drug use and debauchery, the film was dishonoring the name of Lord Krishna and Lord Rama.

EAST MEETS WEST

Hare Rama Hare Krishna seems to portray the West as a source of problems for Indians. Whenever any of the lead characters embrace Western values or lifestyle, it leads only to a tragic turn of events. This pessimistic outlook reflects the perception, held by many Indians at the time, that the West was a threat to the culture and traditions of the East.

Srila Prabhupada, however, tackled the challenge in his own way. From a spiritual perspective, Prabhupada didn’t make a distinction between East and West. To him, all living beings were all children of Krishna, and all equal candidates for Krishna’s mercy. And so, at an age when most people would consider retirement, he left India and set sail for America. He didn’t travel there for his own enjoyment or because he was enamored by the opulence of the West; he went in order to share the spiritual treasures of India with the rest of the world. He went to give, not to take. This was the instruction that this own guru, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, had given him, following in the footsteps of Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, who had predicted 500 years earlier that the holy name of Krishna would one day reach every town and village of the world.

From a practical point of view as well, Prabhupada favored harmonizing the best of Indian and Western gifts. He often quoted the allegory of a blind man and a lame man. Individually, each was limited by his disability. But when they worked together so that the lame man climbed atop the shoulders of the blind man, they could both move forward. Similarly, Prabhupada explained, India had spiritual insights to offer the world but was hampered by a lack of material resources. The West, on the other hand, had strong infrastructure and resources but was suffering from lack of a clear spiritual vision. If the two could work together, he suggested, the whole world could be spiritually uplifted.

When the prestigious New York Times newspaper covered ISKCON’s Ratha-yatra festival in New York City, they headlined the story “East Meets West.” Prabhupada was so pleased that he asked disciples to purchase additional copies and send them to friends and supporters and prominent people in India. Why? Prabhupada appreciated that the newspaper had understood the essence of his mission and the reason he had journeyed to America: to bring East and West together, under the common banner of God consciousness.

FAST-FORWARD

If we fast-forward 40 years from the historic release of Hare Rama Hare Krishna, how far have we come? Some things, of course, remain the same. “Dum Maro Dum” is still a popular song, and for better or worse may remain so for many years to come. Westerners seeking spiritual alternatives (or simply an exotic holiday) still flock to India. And certainly some Indians still have mixed feelings about this.

But many things have changed too. Thanks largely to globalization, economic forces, and the pervasiveness of the internet, the distance between India and the West has become far shorter. The West is not nearly the same source of mystery and fear that it once was.

Today, the sight of a white-skinned bhakta walking down the busy streets of Mumbai or Chennai hardly raises an eyebrow. Far from being viewed with suspicion or ridicule, today ISKCON is one of the most respected and dynamic spiritual organizations active in India. In places like Mumbai, New Delhi, Chennai and Tirupati, ISKCON has built huge cultural centers that celebrate and promote India’s spiritual heritage and teach people how to apply Vedic wisdom in the modern age. Today, ISKCON runs the world’s largest vegetarian food relief program; ISKCON’s Indian temples are leading the way in working to eradicate hunger and poverty especially through innovative midday meals programs.

The rest of the world is a different place as well. Throughout America and Europe, interest in India’s spirituality is at an all time high, but in a very different way than it was back in the 1960s and 1970s. Practices that were considered radical and on the fringe back then like meditation, vegetarianism, believing in reincarnation, or chanting mantras are today considered mainstream. Surveys indicate that as many as 30 million people in America alone practice yoga today. The Bhagavad-gita is considered a must-read for those who fashion themselves educated citizens of the world; even US President Barack Obama mentioned reading the Gita in his autobiography. Kirtana is quickly becoming one of the most popular forms of music, and there was recently a proposal made that it be given it’s own category in the famous Grammy Awards.

The westerners taking part in these practices today are not the hippies and drop-outs of yesteryears. Visit a yoga class, Bhagavad-gita discussion, kirtana concert, or a satsanga at any of the thousands of yoga studios throughout America. You will find it filled with CEOs, lawyers, doctors, college professors, artists, and even a scientist or two.

Of course, this spiritual renaissance is the result of many cultural and social forces at work. But it is also due, in no small part, to the efforts of those first devotees of the Hare Krishna movement in the 1960s and 1970s. We are only now beginning to see the fruits of some of the seeds that these pioneers planted forty years ago.

Investment bankers carry a japa-mala in their briefcases. Executives of Fortune 500 corporations fill their social calendars with yoga retreats and pilgrimages. Champion athletes conclude their workouts by assuming a lotus position and practicing meditation for hours on end. It may sound fantastic, but in this case truth may indeed be stranger than fiction.

It comes off as a great story, and one that a filmmaker looking to make a hit Bollywood sequel might want to consider telling on the big screen.

Vineet Chander (Venkata Bhatta Dasa) is the Director of the Hindu Life Program at Princeton University. An attorney and communications consultant, he formerly served as the Director of Communications for ISKCON in North America.