The pure devotee's first month in the West. "Who would expect to meet a svami in someone's living room in Butler, Pennsylvania? It was just really tremendous. In the middle of middle-class America. "

Srila Prabhupada was met at the dockside by a man from Travelers Aid who escorted him to the Port Authority Bus Terminal. New York's midtown streets were far more intense than the Boston pier. Assisted by the guide, Srila Prabhupada got on the "Pittsburgh" bus. Travelers Aid paid the fare and was reimbursed by Mr. Gopal Agarwal.

The bus came swinging out of the terminal and rode in the shadows of skyscrapers through asphalt streets crowded with people, trucks, and automobiles. Then it entered the Lincoln Tunnel under the Hudson River and emerged on the Jersey side. Then down the Jersey Turnpike, past fields of huge oil drums, the Manhattan skyline visible on the left, while six lanes of traffic sped sixty miles an hour in each direction. Newark Airport came up close by on the right, with jets visible on the ground. Electric power lines spanned aloft between steel towers into the horizon.

Srila Prabhupada had never seen anything like this in India. He could now understand by direct perception that America was a passionate culture. As described in Bhagavad-gita, "The mode of passion is born of unlimited desires and longings, and because of this one is bound to material fruitive activity." For Srila Prabhupada it was a scene of madness. What was the important business for which people were rushing north and south at breakneck speed? It was not for service to Krsna, but for material sense gratification. He could see the goals of the people advertised on their billboards.

On the highway from Delhi to Vrndavana, there are comparatively few signs. One sees mostly the land, roadside streams, temples, and farmers working in the fields. Most people on the road travel by ox cart or on foot, and in Vrndavana even the ordinary passers-by greet each other by calling, "Jaya Radhe," "Hare Krsna." But here on the Jersey Turnpike there were fields full of factories and huge oil drums, and billboards everywhere. Of course, by 1965 there were already plenty of factories outside Delhi, but the cumulative effect did not pack anywhere near the materialistic punch of the route from New York to Pittsburgh.

We should not think that Srila Prabhupada was simply an Indian citizen suffering from cultural shock. Coming from Vrndavana, which is virtually the spiritual world, he was immersed in Krsna consciousness. By his spiritual standards, these factories of the American Northeast were places of ugra-karma—bitter, unnecessary work that entangled passionate human beings and produced only hellish conditions. What Srila Prabhupada saw proudly glamorized on mile after mile of billboards were the basic pillars of sinful life he had come to preach against—meat-eating, illicit sex, intoxication, and gambling. The signs promoted dozens of brands of liquor and cigarettes, roadside restaurants offered slaughtered cows in the form of hamburgers, and no matter what the product, it was usually advertised by the form of a woman to appeal to the appetite for sex. Srila Prabhupada, however, had come to teach the opposite, to teach that happiness is not found in passionate endeavors, and that only when one becomes detached from the mode of passion, which leads to sinful acts, can one become eligible for the happiness the soul enjoys in relation to Krsna.

Looking out the window of the bus, Srila Prabhupada saw the advancement of degradation and ignorance of life's real purpose. Since he was a preacher of the Bhagavatam, his thoughts while encountering these American scenes must have resembled those expressed thousands of years ago by the pure devotee Prahlada Maharaja, who prayed to the Lord, "I see that there are many saintly persons indeed, but they are interested only in their own deliverance. Not caring for the big cities and towns, they go to the Himalayas or the forests to meditate with vows of silence. They are not interested in delivering others. As for me, however, I do not wish to be liberated alone, leaving aside all these poor fools and rascals. I know that without Krsna consciousness, without taking shelter of Your lotus feet, one cannot be happy. Therefore I wish to bring them back to shelter at Your lotus feet."

After an hour or so, the scenery changed to the mountainous countryside of Pennsylvania, and the bus went through long tunnels in the mountains. After night arrived, the bus suddenly entered the heavily industrialized Pittsburgh area, on the shore of the Allegheny River. Srila Prabhupada couldn't clearly see the structures or activity of the steel mills, but he could see their lights and occasionally their industrial fires or smokestacks. Millions of lights shone throughout the city's prevailing dinginess.

When Srila Prabhupada's bus arrived at the terminal, it was past midnight. Mr. Gopal Agarwal, his sponsor, was waiting with the family's Volkswagen bus to drive him to Butler, about an hour north. To host Srila Prabhupada in his home was not Gopal's idea; he had been requested to do so by his father, a businessman who lived in Mathura, India, and who had a fondness for sadhus (saintly persons) and religious causes.

To visit America without assured employment, an Indian had to have proof of financial sponsorship in the United States. Accommodating differentsadhu acquaintances, the senior Mr. Agarwal had a number of times sent sponsorship papers for Gopal's signature, and Gopal had obediently signed them—but nothing had ever come of them. Srila Prabhupada's friendship with Mr. Agarwal of Mathura was not very involved. They had met briefly, and when Srila Prabhupada spoke of going to America, Mr. Agarwal said he would write his son about it. Later, he produced for Srila Prabhupada the sponsorship letter.

The unsuspecting Agarwals of Butler were "simple American people," according to Mrs. Sally Agarwal, who had met her Indian husband while he was working as an engineer in Pennsylvania. They sent back the sponsorship letter for A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami thinking that this was the last they would hear of it; they had no idea he would travel across the ocean and enter the country on the strength of their sponsorship.

About a week before Srila Prabhupada was to reach Butler, a letter arrived. Mrs. Agarwal opened it and then, in alarm, called her husband. "Honey, sit down. Listen to this: the svami is coming." Srila Prabhupada had sent his picture so that they would not mistake him when he came in. They thought the picture was frightening. "There'll be no mistake there," Gopal had said.

The whole event was quite a shock for the Agarwals. What would they do with an Indian svami in their home? But there was no question of notaccepting him; they were bound by the request of Gopal's father. So Gopal had dutifully purchased Srila Prabhupada's ticket from New York to Pittsburgh and arranged for the agent from Travelers Aid to meet him at the dock in New York. Later he drove to meet the strange sadhu at the Pittsburgh bus terminal.

Gopal's first impression of Srila Prabhupada, he later recalled, was that he was not unusual. Although perhaps he had never met a Vaisnava sadhuquite like this, Gopal had seen many, many sadhus before in India. But in any case he had certainly never received one in his home in America. It was about three in the morning when they started from Pittsburgh to Butler.

In 1965 the population of Butler was about twenty thousand. Butler is an industrial city located amid hills in an area rich with oil, coal, gas, and limestone. At the time, its industry consisted mainly of the manufacture of plate glass, railroad cars, refrigerators, oil equipment, and rubber goods. (Butler is also famous as the town where the U.S. Army Jeep was invented in 1940. A granite memorial in the park bears the inscription "Butler, Pennsylvania, Home of the Jeep.") Ninety percent of the people in the local industries were native Americans. The nominal religion had always been Christian, mostly Protestant with some Catholic, and in later years a few synagogues had appeared. There was surely no Hindu community at that time. In fact, Gopal asserts he was the first Indian to move to Butler.

As Gopal Agarwal pulled into town with Srila Prabhupada on the warm, humid morning of September 21, it was long before sunrise. The morning edition of the Butler Eagle was getting ready to go to the stands. The front page would carry three stories on India: "Red Chinese Fire on India," "Prime Minister Shastri Declares Chinese Communists Out to Dominate World," and "United Nations Council Demands Pakistan and India Cease Fire in 48 Hours."

Srila Prabhupada arrived at 4:00 A.M., and the Agarwals invited him to sleep on the couch in their living room. The Agarwals, who had lived in Butler a few years, had two very young children and now felt established in a good social circle. They were living in a townhouse known as Sterling Apartments, and their place consisted of a small living room, a dining room, a kitchenette, two upstairs bedrooms, and a bathroom. They decided that since their apartment had so little space, it would be better if the svami slept at a room at the Y.M.C.A. and came to visit them during the day. But living space wasn't the real difficulty—it was him. How would he fit into the Butler atmosphere? He was their guest, so they would have to explain him to their friends and neighbors.

It was a fact that Srila Prabhupada was immediately a great curiosity for whoever saw him. In anxiety, Mrs. Agarwal decided that instead of having people speculate about the strange man in orange robes who was living at their house, it would be better to let everybody know about him from the newspapers. Mrs. Agarwal says that she openly related her plan to Srila Prabhupada, who laughed with good humor, understanding that he didn't quite fit in.

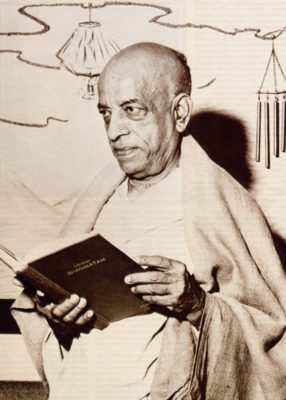

So Sally Agarwal hurried Srila Prabhupada off to a Pittsburgh newspaper office, but unfortunately the first woman who interviewed him simply wasn't able to comprehend why Mrs. Agarwal thought this person would make an interesting story. Mrs. Agarwal then took Srila Prabhupada to the local Butler Eagle, where he was interviewed more avidly. On September 22 a feature article ran in the Butler Eagle. "In Fluent English," the headline read, "Devotee of Hindu Cult Explains Commission to Visit the West." A photographer had come to the Agarwals' apartment and taken a picture in the living room, showing Srila Prabhupada standing in front of a wall plaque decorated with Chinese lanterns. In this first news photo in America he is holding an open volume of Srimad-Bhagavatam, and the caption reads, "Ambassador of Bhakti-yoga."

The article begins, "A slight brown man in faded orange drapes wearing white bathing shoes stepped out of a compact car yesterday and into the Butler Y.M.C.A to attend a meeting. He is A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swamiji, a messenger from India to the peoples of the West." The reporter refers toSrimad-Bhagavatam as "Biblical literature" and quotes Srila Prabhupada as saying, "My mission is to revive people's God consciousness. God is the Father of all living beings, in thousands of different forms. Human life is a stage of perfection in evolution; if we miss the message, back we go through the process again."

The reporter describes Srila Prabhupada's personal habits in some detail: "Bhaktivedanta lives as a monk, and permits no woman to touch his food. On a six-week ocean voyage and at the Agarwal apartment in Butler he prepares his meals in a brass pan with separate levels for steaming rice, vegetables and making 'bread' at the same time. He is a strict vegetarian, and is permitted to drink only milk, the 'miracle food for babies and old men,' he noted."

The article continues, "The Swamiji is equally philosophical about physical discomforts or wars: 'It's man's nature to fight,' he shrugs. 'We have to adjust to these things; currents come and go in life just as in an ocean.' " The article ends, "If Americans would give more attention to their spiritual life, they would be much happier, he says."

The Agarwals had their own opinion of why Srila Prabhupada had come to America. They thought that it was just to finance his books, and that was all. They did not think he wanted to draw any devotees. He had no idea of starting a world movement and creating followers who would chant Hare Krsna in public, they felt. They never saw him with karatalas (hand cymbals) or a drum, and they maintained the impression that he was hoping only to meet someone who could help him with the publication of hisSrimad-Bhagavatam. At least they hoped he wouldn't do anything to attract attention, and they felt that this was his mentality also. "He didn't create waves," Sally Agarwal says. "He didn't want any crowd. He didn't want anything. He only wanted to finance his books." Perhaps Srila Prabhupada, seeing their nervousness, agreed to keep a low profile just out of consideration for his hosts.

At Srila Prabhupada's request, however, Mr. Agarwal allowed an open house in his apartment every night from six to nine.

It was quite an intellectual group that we were in (Sally Agarwal relates), and they were fascinated by him. They hardly knew what to ask him. They didn't know enough. This was just like a dream out of a book. Who would expect to meet a svami in someone's living room in Butler, Pennsylvania? It was just really tremendous. In the middle of middle-class America. My parents came from quite a distance to see him. We knew a lot of people in Pittsburgh, and they came up. This was a very unusual thing, having this man here. But the real interest shown in him was only as a curiosity.

He had a typewriter, which was one of his few possessions, and an umbrella. That was one of the things that caused a sensation, that he always carried an umbrella. And it was a little chilly and he was balding, so he always wore this hat someone had made for him, like a swimming cap. It was a kind of sensation. And he was so brilliant that when he saw someone in a car twice, he knew who they were—he remembered. He was a brilliant man. Or if he met them in our apartment and saw them in a car, he would remember their name, and he would wave and say their name. He was a brilliant man. All the people, they liked him. They were amazed at how intelligent he was. The thing that got them was the way he remembered their name. And his humorous way. He looked so serious all the time, but he was a very humorous person…. He was forbidding in his looks, but he was very charming.

He was the easiest guest I have had in my life, because when I couldn't spend time with him he chanted and I knew he was perfectly happy. When I couldn't talk to him he'd chant. He was so easy, though, because I knew he was never bored. I never felt any pressure or tension about having him there. He was so easy that when I had to take care of the children he would just chant. It was so great. When I had to do things, he would just be happy chanting. He was a very good guest. When the people would come, they were also smoking cigarettes, but he would say, "Pay no attention. Think nothing of it. " That's what he said. "Think nothing of it. " Because he knew we were different. I didn't smoke in front of him, because I knew I wasn't supposed to smoke in front of Gopal's father so I sort of considered him the same. He didn't make any problems for anybody.

Gopal remembers that at one evening meeting a guest asked Srila Prabhupada, "What do you think of Jesus Christ?" And Srila Prabhupada replied, "He is the son of God." Then he added that he himself was also a son of God. Everyone was interested to hear that he did not disagree that Jesus Christ was the son of God. "His intent was not to have you change your way of life," Gopal says. "He wasn't telling anybody they should be vegetarian or anything. All he wanted you to do was to follow what you are but be better. He didn't stress that we should give up many things."

Mrs. Agarwal remembers that in speaking, Srila Prabhupada would often tell funny stories, using animals like goats and pigs to illustrate philosophical points. She gradually developed a real friendship and admiration.

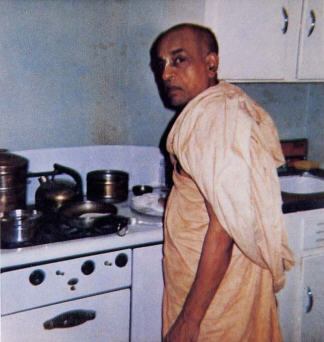

While Srila Prabhupada was in Butler he followed a regulated daily schedule. Every morning he would walk the six or seven blocks from the Y.M.C.A to the Sterling Apartments and arrive there about 7:00 A.M. (The Agarwals remember that when he first arrived from India he was carrying a large bundle of dried cereal that appeared like rolled oats. This supply was intended to last him for some time, and every day he would take some with milk for his breakfast.) About 7:45, Gopal would leave for work, and then Srila Prabhupada would start to prepare his lunch in the kitchen. Without using a rolling pin, he would make capatis (a kind of bread) by clapping the kneaded dough in his hands. He worked alone for two hours while Mrs. Agarwal did housework and took care of her children. Srila Prabhupada took his prasada at 11:30.

When he cooked he used only one burner (Mrs. Agarwal relates), and I asked him why he was cooking that way. He said, "Well, when one becomes a svami he gives up any contact with women. " Since he was only cooking for himself he only needed to use one fire. The bottom-level pot created the steam; he had the dal [a kind of soup] on the bottom, and it created the steam to cook many other vegetables. So for about a week he was cooking this great big lunch, which was ready about 11:30, and Gopal always came home for lunch about twelve. I used to serve Gopal a sandwich, and then he would go back to work. But it didn't take me long to realize that the food the svami was cooking we'd enjoy too, so he started cooking that noon meal for all of us. Oh, and we enjoyed it so much.

Our fun with him was to show him what we knew of America, and he had never seen such things. It was such fun to take him to the supermarket. He loved opening the package of okra or frozen beans and he didn't have to clean them and cut them and do all those things. He opened the freezer every day and just chose his items. It was fun to watch him. He sat on the couch while I swept with the vacuum, and he was so interested in that, and we talked for a long time about that. He was so interesting. So every day he'd have this big feast, and everything was great fun. We really enjoyed it. I would help him cut the things. He would spice it, and we would laugh. He was the most enjoyable man, most enjoyable man. I really felt like a sort of daughter to him, even in such a short time. Like he was my father-in-law. He was a friend of my father-in-law, but I really felt very close to the man. He enjoyed everything. I liked the man. I thought he was tremendous.

After his lunch Srila Prabhupada would leave the house about 1:00 P.M. and walk to the Y.M.C.A., where the Agarwals figured he must have worked at his writing from one until five. He would come back to their apartment in the early evening, about six o'clock, after they had taken their meal. Since they ate meat, Mrs. Agarwal was careful to have it cleared away before he came. One night he came early, and she said to him, "Oh, Swamiji, we have just cooked meat, and the smell will be very disagreeable to you." But he said, "Oh, think nothing of it. Think nothing of it." In the evening Srila Prabhupada would meet any guests who came to speak with him, and he would ask the Agarwals to prepare warm milk with sugar for him at 9:00 P.M. Even if the guests were taking coffee and other things, he would request a glass of warm milk. He would speak until nine thirty or ten, and then Mr. Agarwal would drive him back to the Y.M.C.A. So every day Srila Prabhupada would walk between the Y.M.C.A. and the Agarwal home three times and ride back in their car in the evening.

Srila Prabhupada would also do his own laundry every day, washing his clothes in the Agarwals' bathroom and hanging them up outside. He sometimes also went with the Agarwals to the laundromat and was interested to see how the people washed and dried their clothes there. "He was very interested in the American ways and the people," Mrs. Agarwal says.

Our boy was six or seven months old when the Svami came (Mrs. Agarwal relates). And the Indians love boys. The Svami liked Brij. He was there when Brij first stood. The first time Brij made the attempt and actually succeeded, the svami stood up and clapped and clapped. It was a celebration. Another time our baby teethed on the svami's shoes. I thought, "Oh, those shoes. They have been all over India, and my kid is chewing on them. " You know how a mother would feel.

Almost every night he used to sit in the next-door neighbor's back yard. We sat out there sometimes with him. Or we stayed in the living room. In October the air got cool. (He arrived about the twentieth of September and stayed with us until the middle of October.) One time something happened with our little girl, Pamela, who was only three years old. I used to take her to Sunday school, and she learned about Jesus in Sunday school. Then when she would see Svamiji with his robes on and everything, she called him Svami Jesus. And this one time when it first dawned on us what she was saying, she called him Svami Jesus, and Swami smiled and said, "And a little child shall lead them. " It was so funny.

While in Butler, Srila Prabhupada spoke on Krsna consciousness to various groups in the community. He addressed the Lions International, and the group presented him with a formal document dated October 6, 1965: "Be it known that A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami was a guest at the Lions Club of Butler, Pa., and as an expression of appreciation for services rendered the Club tenders this acknowledgement." He also gave a talk at the Y and at a small college in Herman, Pennsylvania, and he was always ready to speak to guests who came to visit him at the Agarwal home.

There are no available recordings of any of the Butler talks, but weknow what Srila Prabhupada spoke. He spoke the same eternal message ofBhagavad-gita that has come down in disciplic succession from Krsna. As he had already informed the people of Butler through the Butler Eagle, "My mission is to revive people's God consciousness. God is the Father of all living beings in thousands of different forms. Human life is a stage of perfection in evolution; if we miss the message, back we go through the process again."

The lectures in Butler were valuable for Srila Prabhupada because they gave him his first indication of how his message would be received in America. In his poem written at the Boston pier he had stated the principle by which he would become successful: "I am sure that when this transcendental message penetrates their hearts they will certainly feel gladdened and thus become liberated from all unhappy conditions of life." But now the principle was actually being tested in the field. Was it possible—would they be able to understand? Were they really interested? Would they surrender?

From all available evidence it appears Srila Prabhupada was quite pleased with the results of his talks in Butler. It is difficult to know his thoughts, since he made no diary entries and as yet had no intimate disciples to share his meditations on preaching. The Agarwals, for all their kindness, did not share in his plans to create a worldwide Krsna consciousness movement. Rather, they were convinced that Srila Prabhupada had no intention of making followers.

A letter written by Srila Prabhupada a month after he left Butler reveals some of his thoughts about his stay in the Pennsylvania town. He wrote to Sumati Morarjee, who had provided his passage to America, "By the grace of Lord Krsna the Americans are prosperous in every respect. They are not poverty-stricken like the Indians. The people in general are satisfied so far as their material needs are concerned, and they are spiritually inclined. When I was in Butler, Pennsylvania, about five hundred miles from New York City, I saw there many churches, and they were attending regularly. This shows that they are spiritually inclined. I was also invited by some churches, church-governed schools and colleges, and I spoke there, and they appreciated it and presented me some token rewards. When I was speaking to the students, they were very much eagerly hearing me about the principles of Srimad-Bhagavatam. Rather, the clergymen were cautious to allow [that is, about allowing] the students to hear me so patiently. They thought that (they should be careful so that] the students may not be converted into Hindu ideas, as it is quite natural for any religious sect. But they do not know that devotional service of the Lord (Sri Krsna) is the common religion of everyone, including the aborigines and cannibals in the jungle."

This letter indicates that Srila Prabhupada was quite hopeful. He had spoken, and the young people, especially, were receptive. The American people were not so impoverished as to think only of economic development, and in fact they had an attitude of spiritual inquiry. "I give you my frank admission," Srila Prabhupada wrote, "that when I was in India I was thinking the Americans may be a different type of people or they may be thinking in other ways. They may be different in so many ways. But here I see there is no difference at all. Only some bodily features. Your people are fair complexioned, your bodies are white, and they are also colored. In India also you will find varieties of color, beginning from the American, European color down to the black Negro color. Even when I study the pigeons, I see, 'Oh, these same pigeons are playing just like Indian pigeons.' Even I see the sparrow—there is no difference." The Americans, for all their advertised opulence and advancement, were the same materially conditioned souls found anywhere else in the universe. This Srila Prabhupada discovered firsthand in Butler. If for nothing else, Butler was important to Srila Prabhupada because it was the first testing ground for the Hare Krsna movement.

Near the end of his stay in Butler, Srila Prabhupada received a letter from Sumati Morarjee. Dated October 9 from "Scindia House" in Bombay, the letter read as follows:

"Poojye [Respected] Swamiji,

I am in due receipt of your letter of the 24th ultimo. And glad to note that you have safely reached the U.S.A., after suffering from seasickness. I thank you for your greetings and blessings. I hope by now you must have recovered fully from the sickness and must be keeping good health. I was delighted to read that you have started your activiites in the states and had already delivered some lectures. I pray to Lord Bal-Krishna to give you enough strength to enable you to carry the message of Sri Bhagavatam. I feel that you should stay there till you fully recover from your illness and return only after you have completed your mission.

Here everything is normal. With respects,

Yours sincerely,

Sumati Morarjee"

Srila Prabhupada regarded the last recommendation in this letter as being especially significant: his well-wisher was urging him to stay in America until he had completed his mission. When Srila Prabhupada had first entered America and the immigration officials had asked him how long he intended to stay, Srila Prabhupada had not yet made firm plans. "I have one month's sponsorship in Butler," he thought, "and then I have no support. So perhaps I can stay another month." So he had told the immigration officials he would stay in America for two months. Sumati Morarjee, however, was urging him to stay on, and it was a fact that the prospects of preaching to the Americans seemed good, although if he were to stay he would need support from India, from persons like Sumati Morarjee. There was no question of staying simply to sightsee; he wanted to do something wonderful. He had many plans. But now it was time to leave Butler.

Srila Prabhupada decided to move to New York City, although he wanted first to visit Philadelphia, where a meeting had been arranged for him with a Sanskrit professor, Dr. Norman Brown, at the University of Pennsylvania.

Mrs. Agarwal was sorry to see him go.

After a month I really loved the svami (Mrs. Agarwal relates). I felt kind of protective in a way, and he wanted to go to Philadelphia. But I couldn't imagine—I told him—I could not imagine this man going to Philadelphia for two days. He was going to speak there, and then to New York. But he knew no one in New York. If the thing didn't pan out in Philadelphia, he was just going to New York, and then there was no one. I just could not imagine that man … it made me sick. I remember the night he was leaving, about two in the morning. I remember sitting there as long as he could wait before Gopal took him to Pittsburgh to get on that bus. Gopal got a handful of change, and I remember telling him how to put the money in the slot so that he could go up to the bus station to take a bath, because he was supposed to take a bath a few times a day. And Gopal told him how to do that, and told him about the automat in New York. He told him what he could eat and what he could not eat, and he gave these coins in a sock, and that's all the man left us with.

Praying to be the puppet of Krsna, Srila Prabhupada was now moving on, not exactly under his own direction. Why had he gone to Butler? Why was he going to New York? He could see it was not merely his own decision; it was happening by Krsna's grace. As Krsna's pure devotee, he wished to be merely an instrument, in the Lord's hands, for distributing Krsna consciousness. As a sannyasi, of course, he was quite accustomed to picking up and leaving one place for another. As a mendicant preacher he had no remorse about leaving behind the quiet life of walking to and from the Butler Y.M.C.A., nor any attachment for the domestic habitat where he would cook and talk with Sally Agarwal about vacuum cleaners, frozen foods, and American ways.

Now it was necessary that he go more on his own and try to preach in one of the biggest cities in the world. His stay in Butler helped him get his first idea of America and gave him confidence that his health was strong and his message communicable. He was glad to see that America had practically everything necessary for his Indian vegetarian diet, and that people could understand his English. He had learned that the program of giving casual one-time lectures here and there was very limited, and he had also found that although there would be opposition from the established religions, people individually were very interested in what he had to say. Now he had to go and find out more of what Krsna had in mind for him.

"He was a very happy man," Mrs. Agarwal remembers. "Very happy. If he'd had any idea of what the future was, he would not have believed it. That's what I think. He was a very humble, modest man. I think he had no idea."