>

>

If it's been some years since you last visited an art exhibit, you may be in for a surprise. Far from a Da Vinci or Michelangelo rendering of a pastoral scene or the Pieta, you're likely to see an oversized ceramic cigarette butt, or maybe a 7,200-meter line (drawn on paper and rolled into a chrome-plated can for display), or perhaps a couple of realistic vinyl eyeballs, or an empty canvas, or… nothing at all the artist's statement may be to lock you out of the gallery.

Art critic and lecturer Peter Hawkins says, "One New York artist did his piece de resistance by going into the Museum of Modern Art and spraying Picasso's Guernica with dayglow paint. They put him in jail, but he got reviews in all the art magazines. Now his work is in great demand." Says Hawkins, an associate of London's Royal College of Art, "What's been happening is that people have been using art to sell their products, and now art itself has become just another product. For an artist in a money-oriented society, the most important thing is selling. His bread and butter depends on whether someone's going to buy his painting. So if he's going to survive as an artist, he's forced to come up with the unusual, the bizarre. He ends up literally battling with other artists for recognition. He has to sacrifice something his integrity to attract attention to himself."

According to Hawkins, artists haven't always been in such a plight. "If we look back into our history as far as we can see," he says, "art was an expression of an inner vision, it was a kind of sacrifice to the divine. The ancient Greeks worshiped and honored Athena in their artwork. The early Christian artists, up to the Renaissance, painted exclusively about Christ. When people came to see their work painted on a church wall, they became enthralled with devotion. Even during the Renaissance, when artists like Da Vinci became scientists, they used their discoveries of new techniques to evoke a sense of devotion in their viewers. As soon as the Florentine artists discovered perspective in painting, they used it to depict the life of Christ more realistically. Techniques were never ends in themselves. Wherever you look before the Renaissance, you'll find that artists were painting with devotion. Instead of attracting attention to themselves, they attracted attention to God."

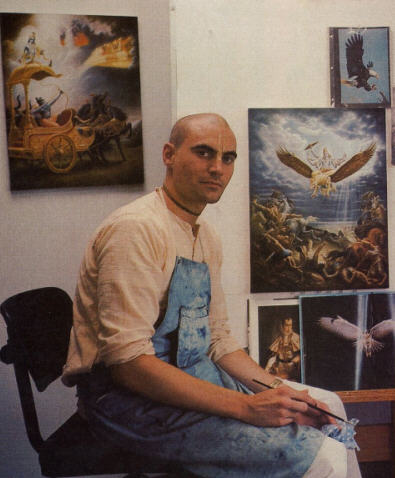

Nathan Zakheim, art consultant for the University of California and the city of San Francisco, claims that the devotional spirit in art is still alive. "We have an Athens here," says an enthusiastic Zakheim about the art academy he directs in a palm-lined section of West Los Angeles. "We're trying to have that open forum where our work flows naturally from our purpose in living. All the artists here paint from a spirit of devotion that's continually expanding."

Zakheim (Nara-narayana dasa) agrees with critic Hawkins that traditionally, art was mystical and austere. "But gradually," he says, "artists started flattering and catering to their patrons. Fine art lost its devotional and mystical quality when artists started trying just to satisfy their wealthy patrons. So in terms of art history, our academy is harking back to that original concept painting to express a higher reality and to bring out the natural sense of devotion in the person who sees it."

The academy Zakheim directs began in the late sixties, when His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada came to America to introduce ancient India's Vedic culture the wisdom of the Bhagavad-gita and the chanting of the Hare Krsna mantra. While still in India preparing for his task, Srila Prabhupada had called for "a cultural presentation for the re-spiritualization of the entire human society… There is a need," he wrote, "for a spiritual atmosphere… a clue as to how humanity can become one in peace, friendship and prosperity with a common cause."

"Srila Prabhupada founded the art academy," says Zakheim, "upon that spirit of a 'common cause.' What's unique here is that all of us who paint see our work as part of a greater art practicing the yoga of devotion. We paint from a desire to understand our higher selves, our spiritual selves, and to relate to others on that higher level. So our artwork stays free from the kind of nihilistic imagery that assaults you when you walk into a gallery today. We're trying to produce an art that is positive, creative, and inspirational."

Five hundred years ago, Michelangelo expressed a similar thought. "True artistic inspiration," he said, "is not derived from the material world. The visible world has value only in reflecting the divine idea."

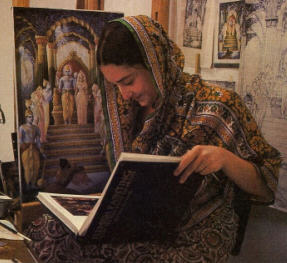

The artists at the academy are currently painting passages from an ancient 18,000-verse epic called Srimad-Bhagavatam (The Beautiful Story of the Personality of Godhead). Written in Sanskrit and translated into English by Srila Prabhupada, the Bhagavatam is India's greatest spiritual classic. It describes the all-attractive personal nature of the absolute, Sri Krsna, and the highly evolved spiritual life-styles that attraction for Krsna inspired in people. "If you're sensitive to the sublime personal relationships found in the Bhagavatam," Zakheim says, "you'll expand your own awareness thousands of times. As artists, we're trying to paint these historical personalities in a way that's as authentic as possible. By illustrating their spotless character and way of living, we're trying to show them some respect. That in itself will be sufficiently evocative."

Whether the academy's paintings create a significant impact in the art world remains to be seen. Already, however, a few critics have spoken highly of them. After viewing some of the paintings, Professor John La Plante of Stanford University termed them "works of art of a higher visual order. They have," he said, "a remarkable sense of realism. They're not painted in the symbolic manner that's common in Indian paintings; rather, they contain a visual precision which is amazing. The images are so convincing that they quit being symbols and become reality."

Mr. Burton Frederickson, the curator of California's J. Paul Getty Museum, found the academy's paintings "fascinating. I am impressed that the artists are reviving traditional techniques similar to those used by classical artists. The traditional aspects of the craft are pretty much forgotten today, and the academy's efforts to revive them are very commendable."

Royal College associate Peter Hawkins observes that the paintings are "saturated with devotion. The quality of devotion seems to vibrate in them." Hawkins compares them with the works of Fra Angelico, whose frescos depicting the life of Christ are world-renowned. For Hawkins, the academy's paintings "need to be felt within the heart rather than directly perceived with the eye. I feel that I'm looking into a purely spiritual space. With each viewing I'm learning something new."

With techniques that have been all but forgotten, and imagery that is startlingly new to Western viewers, the academy's art promises to create quite a stir. "Some will say we're turning the clock back a hundred years," says Zakheim, "while others will call it the most progressive art movement of the day. That's not so important to us. We're not trying to make popular images. What we are trying to do is get a kind of introspection and inspiration from God, who we hope will guide us to a clearer and clearer understanding of how to paint. If somehow we have that inspiration, naturally people who see our work will also become inspired. They'll see that all over the world we need a spiritual standard of living to free us from our malaise. And when that happens, there will be a Renaissance to end all renaissances!"