A veteran reporter confronts some key environmental issues.

Tom Hacknead, a veteran reporter for the Daily Trash in Los Angeles, felt restless. He'd been covering events at the city morgue for twenty years and needed a change. One Monday morning an article in Newsbleak magazine on environmental catastrophes caught his eye. "That's it!" he thought, "I'll become an environmental expert and focus on the dying biosphere instead of on dead people."

From Newsbleak, Tom learned that a blanket of pollution created by the burning of fossil fuels such as coal and oil was enveloping and slowly suffocating the earth. To halt the buildup of this blanket, experts advised (Tom always quivered with excitement at the word "expert") that we rely more on nuclear energy, which generated radioactive waste instead of carbon dioxide.

Trouble was, Newsbleak continued, the disposal of radioactive wastes was an "explosive issue," since no one wanted any buried in his back yard. "Of course not," Tom mused, with a veteran's humor and insight. "Burying the stuff would turn the earth into a radioactive mattress! And to round things out, we still have that good old-fashioned pillow of smog." Tom was getting a feel for his new turf.

The alternatives to nuclear energy and of fossil fuels, Tom read, were renewable sources like solar energy and hydropower. This information had a mysterious ring to it. What with the L.A. smog, and his office at the Daily Trash having no windows, Tom hadn't seenany sun for ages. He couldn't imagine that sunlight could power his hair dryer or his tanning lamp. As for hydropower, Tom contemplated the faucet in the men's room down the hall but couldn't grasp the concept.

Determined to track down an expert on solar energy and hydropower, Tom called his Aunt Maud in Nevada. "Sure," she told him, "one of the world's leading authorities on sunlight and water is my Daddy's cousin Ezra. He lives about a hundred miles from Reno."

Tom packed his hair dryer and tanning lamp in the trunk of his car. He arrived at the home of Ezra Zukes Livvin late Tuesday afternoon. Ezra Zukes ("E. Z." to his friends) was sitting on his front porch, softly chanting the Hare Krsna mantra on a string of prayer beads. Tom introduced himself as Maud's nephew, accepted a seat beside E. Z., pulled out his pen and pad, and started right in with his questions.

"Mr. Livvin, how long before we'll have generators that can harness the sun's energy efficiently enough to replace, say, nuclear power?"

"How long?" E. Z. looked surprised. "Why look, I've got a whole field full of solar generators that put nukes to shame. Didn't you see?"

Tom noticed for the first time thousands upon thousands of six-foot spikes driven into a field the size of a couple of city blocks. "You built all those yourself?" he asked. "That must have been hard work."

"Not so hard," said Ezra. "I didn't build them. Threw them in last May. Not so hard."

Tom imagined Ezra throwing the spikes from his porch, landing each one perfectly perpendicular, and fairly evenly spaced, across the entire field. "And these things transform sunlight into usable energy?" Tom queried.

"These things are called corn, Mr. Hacknead," said E. Z., a little impatient. "I plant them, water them, harvest them, and…

"Water?" said Tom, his ear sharp for every nuance. "Does that have anything to do with hydropower?"

"Sure," said Ezra, "corn needs sunlight and water to grow. Lord Krsna provides the sunlight. In the Bhagavad-gita He says 'The splendor of the sun, which dissipates the darkness of this whole world, comes from Me.' "

Tom figured Krsna must be another one of Aunt Maud's cousins. "But what about this hydropower?" he pressed, eager to get his story.

"Rain's the best kind of hydropower," said E. Z. "In the Ninth Chapter of the Gita Krsna says, 'O Arjuna, I give heat, and I withhold and send forth the rain.' " E. Z. chuckled, "Around here, Krsna mostly withholds the rain, so I irrigate. But the water still comes from Him."

"And what do you do with the corn power you produce, Mr. Livvin?"

"Feed it to my oxen and the rest of my herd. And I use the oxen, in turn, to plow my corn fields, wheat fields, and my favorite-the zucchini patch. The Gita says that plowing and cow protection are the first duties of the business community, before trade, banking, nuclear power, and all that. Who needs nukes? With just solar energy and hydropower, I generate corn power, wheat power, ox power, milk power, and zucchini power."

Tom found Ezra's expertise intimidating, but drawing on his experience interviewing coroners, he pushed on. "Now, finally, about these oxen . . ."Tom tried in vain to remember, from a grade school course on mammals, what an ox looked like. "Let's see-aardvark, anteater, oxymoron, unicorn.. ."

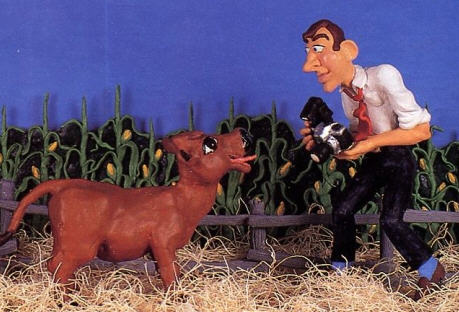

"C'mon, I'll show you," said E. Z. with a sigh, leading Tom across a yard to a red and-white barn.

Stepping inside, Tom drew back. "My goodness," he gasped, "that dog's enormous!"

"That's a calf," said Ezra. "Isn't she pretty?"

Tom had never heard of a calf-dog before. Talk about pollution and waste disposal! he thought. What do you do with a mutt thissize? The sidewalk outside Tom's apartment building in L.A. was always littered with dog feces, but mostly from miniature poodles. Calf-dog indeed!

"How do you dispose of the, uh, droppings from these . . ." Tom began.

"I spread them on my fields," said Ezra. "On your fields," Tom repeated, muffling his surprise. And then, disguising his clinching question with a burst of congeniality, he chortled, "Well, yes, I don't suppose their droppings would be radioactive."

"Nope," said Ezra. "Best fertilizer there is."

"Well, thank you for your time, Mr. Livvin," said Tom, heading for his car. "You're welcome. Hare Krsna. Stay longer if you like," said Ezra.

"Thank you, but no," replied Tom. "I have an article to write."

Piling into his car with his pen and notepads, Tom headed for the highway back to Reno and L.A. What a difficult new subject the environment was. But boy, did he have a story for the Trash.