The morning's at seven,

The hillside's dew-pearled;

Radha-Damodara's on the altar,

And all's right with the world.

(apologies to Robert Browning)

"COWEEEES! COWEEEES!" I call to the three Brown Swiss milking cows as I top the crest to the barn at Gita Nagari. They shake their heads, ringing their brass bells, and reply, "Moo! Mooo! Moo-ooo!" I call their names, "Pre-maaa! Lugi-looo! Hari-leee-la!" They line up at the gate, swishing their tails, and moo at me some more "Hurry up and milk us! We're getting uncomfortable!"

Hare Krsna Devi Dasi

Like so many devotees in the seventies and eighties, when I moved into the temple I never expected to leave. But things changed, and economics and family obligations forced me to leave my beloved Gita Nagari. Thanks to the generosity of the devotees, I found new service I could do, and by leaving Gita Nagari I also gained some understanding of Srila Prabhupada's teaching that devotional service is eternal. My work with Krsna's cows at Gita Nagari is still fresh and vivid in my heart and continues to be a source of inspiration and spiritual nourishment.

Sometimes people say to me, "Oh, I bet you wish you were back with the cows." In one way I do, but in another way I am still with the cows, so I don't feel gloomy and despondent. Greater than my hankering to return to the farm is my wish that thousands or even millions of people could learn the joys of taking care of Krsna's cows. If I could only convey some of those feelings! In this short space I can tell about only a fraction of the experience of one morning, but I hope that even from that you can get some understanding of what it was like. So, back to the barn….

Before I came to the barn today I went to the temple, dressed in my barn pants, flannel shirt, and kerchief, to catch the beginning of the Bhagavatam class. My inspiration is to hear the Jaya Radha-Madhavaprayers before I milk the cows. Now the transcendental melody is in my mind as I climb the milk-house steps in my rubber barn boots. This small cement-block building attached to the barn is a holy place. There's a wonderful photo of Srila Prabhupada descending these same steps when he visited Gita Nagari in July 1976. The milk house is a great place to chant a couple of very loud rounds of Hare Krsna on your beads to get fired up for your service. But not today I'm running late!

I grab a couple of milk cans and rinse them out with a spray of hot water. I dump the sudsy water onto the concrete floor of the milk house, and it swirls down the drain. The milk house always smells clean from bleach and detergent. The milk house has to be absolutely clean so the milk doesn't get contaminated. I rinse out a couple buckets in the sink the white bucket for hand milking and the red one for a hot-water solution for washing the cows' udders. I then hang a cup and a little container of teat dip with iodine over the side of one the buckets.

I dash through the tiny barn office and into the cool barn. Ah! The alfalfa hay and cow manure smell great! Let the city slickers wrinkle their noses they just don't understand the purity of cow manure. I'm not talking about hog manure. My Uncle Mike has a hog farm I know what that smells like! No, I'm talking about cow manure. The Vedas say it's pure. In India a scientist named Dr. Goshal proved experimentally that cow manure has antiseptic properties. Anyway, what a great smell!

Now to get the stalls ready. When Sri Krsna Dasa taught me and Kaulini Dasi how to milk the cows, he said that, just as in Deity worship, the most important things are cleanliness, punctuality, and enthusiasm. First grab a hoe and scrape any manure into the gutter. Then sweep yesterday's hay or grain out of the mangers. Finally, scatter some clean golden straw in the stalls for the cows' bedding. Are the water bowls clean and fresh? Clean, cool water is important for good milk production.

One purifying thing about taking care of cows is that it helps me transcend worrying about my own senses. What do I like? What do I want? Those thoughts are put aside. That's also like Deity worship. Instead of worrying about what I would like, my meditation has to be focused on every-thing that will make the cows comfortable so they'll be relaxed and happy for milking.

The final touch is to put a scoop of sweet-smelling grain into each cow's manger. A cow gets one pound of grain for each three pounds of milk she produces.

Now everything is ready. I grab my trusty stick as I go out the side door to the pasture. I like a stick that's three or four feet long so I can steer my cows easily. I usually carry a stick when I'm around cows, especially cows who know me. Early on, I visited some of my cows in the pasture in the middle of the day. They got excited and frisky and started "horsing" around with one another to show off, and they knocked me to the ground. I wasn't hurt at all, but it showed me that at least a small person like me should carry a stick to keep things under control.

The cows are eager to come into the barn. I unhook the electric fence and encourage them. "Get your grain, Luggy! Come on, Hari Leela! Good girl, Prema!" I steer Hari Leela away from her favorite patch of pig-weed by the barn. Once in the barn, each cow goes automatically to her own stall and starts eating grain. I secure their neck chains to the front of their stalls.

I dash into the milk house to get the buckets. I stop in the office to get some brown paper towels to wash and dry udders. Quickly I pop my favorite milking tape into the barn stereo system Srila Prabhupada singing the Guruvastakam prayers. The cows like everything to be the same every day, and so do I.

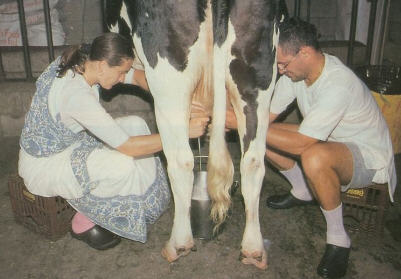

When I was milking three cows, we were still using the mechanized milking system. I would milk Hari Leela and Lugloo by machine and Prema Vihvala by hand. Gita Nagari had been a commercial dairy farm when ISKCON bought it, and we started out milking a lot of cows. Gradually, we decided it wasn't a good idea because we got more bulls than we could train to work. So we started breeding fewer cows. With Prema Vihvala, we began the switch to hand milking. It turned out to be a sweet experience.

In commercial dairying a cow is bred to have a calf once a year. (Unfortunately the dairymen don't care how many bull calves the cows produce, because the bulls are sent for slaughter.) The cow is milked about ten months. When her daily production falls below about thirty pounds (thirty pints), being milked by machine becomes painful, often causing mastitis infection, so they stop milking her just before she has her next calf (or they send her to slaughter). Our cows would never be slaughtered, but Prema was such a loving cow I just wanted to keep milking her when she hit thirty pounds, so Kaulini and I decided to milk her by hand.

Hand milking takes a lot of arm muscle, and I'm a 120-pound weakling. But my desire was great. For a week before the switch, I practiced on my son's hand grips to build my strength. The first week of milking was hard. After that I was fine. Prema was kind and patient. And it was worth it. A dairy cow usually gives fifteen to twenty thousand pounds of milk when she has a calf. But we milked Prema for 643 days, and she gave 25,587 pounds of milk. We were so proud of her!

What was it like to milk her? On the stereo, Srila Prabhupada is singing, "Samsara-davanala-lida-loka …" I approach the stall from the rear, buckets in hand. I lean against Prema's hind quarters as she peacefully munches her grain. "Scootch over, Prema." Clop, clop. She politely steps to the right to make room for me. I sit down on my tie-on spring-coil milking stool. I wash her udder quickly with the hot-water solution, then dry her with a towel. Squirt, squirt. I squeeze each teat, "stripping" the milk into the screened strip cup to get rid of any contamination and check for mastitis globs. The washing and stripping stimulate the cow's milk let-down response and should take about fifteen seconds. We're fine today.

I place the white plastic bucket under Prema's udder. I lean my head into her belly and begin to milk with both hands, not pulling but squeezing thumb and forefinger together at the top of the teat and rhythmically squeezing the milk out with the other fingers. At first her full udder is hard. Squirt, squirt … squirt, squirt … squirt, squirt. She's peaceful as I milk her, keeping time with the music. Srila Prabhupada is singing, and Prema and I are serving Krsna together. Squirt, squirt … squirt, squirt. Most devotee cow milkers hate to waste even a drop of milk. They know the love that goes into making it.

Soon the milk comes out forcefully, rhythmically. Beating on the bottom of the plastic bucket, it sounds like a mrdanga drum going with Prabhupada's singing. When I first started milking by hand, I was surprised how foamy the milk was. It looks so beautiful. Prema's udder is getting soft now as all the milk empties out. The barn cats take their cue and line up on the other side of her, hoping for a squirt. I don't disappoint them. Squirt, squirt right in the mouth. They're surprised and pleased, licking their whiskers.

I'm done milking Prema. Quickly I dip her teats in the iodine solution to prevent mastitis. What will we use for teat dip when we're self-sufficient, I wonder. I lift the heavy milk bucket. This moment is the perfect teacher of humility. I may sometimes think I'm a hotshot devotee, but here's Prema, quietly producing so much milk for the Deities I can hardly lift it. What contribution do I have to compare to that? "Prema Vihvala, you're such a good girl, giving so much milk for Krsna's sweets!" I give her a big hug and pat her heartily. Still munching, she turns to give me an affectionate look.

I give the cats some milk, their reward for protecting the cows' grain from mice. What valuable opportunities there are in this farm life! Even the President of the United States may not get the opportunity to serve Krsna, but here are these scruffy barn cats, every day engaged in devotional service and hearing Prabhupada sing Hare Krsna to their eternal benefit.

Back in the sunny milk house I weigh the milk from each cow and record it on a chart. Production is going up. The cows must love the new spring pasture. Then I pour the white foamy milk through a filter into the milk can. What a beautiful sight! The can goes into the old-fashioned water-cooled can cooler. I think what it might be like to keep the milk fresh as they do in India, by heating it instead of cooling it. A quick cleanup of the milk house, and it's time to take the "girls" out to their daytime pasture.

I unhitch them from their stalls. "Get up! Pasture, Prema! Pasture, Luggy! Get up, Hari Leela!" We amble down the sunny gravel road toward the alfalfa field. I tap the ground with the stick as we walk clomp! clomp! to show them we should be businesslike and not stop and munch too much on the way. Finally we're at the alfalfa field, which is being grazed in small paddocks each day. Today's paddock is about a hundred feet from the road, so the cows are tempted to meander into the adjoining oat field. "Stay on the cow path, Hari Leela!" I tap her on the rear, and she gets back on the path.

She knows what I mean. I taught her "cow path," and I taught the cows "grain" and "pasture." They know what I mean. It's such a simple plea-sure to communicate with them. I feel like a little girl teaching words to her kitten.

I open the electric fence to the lush green alfalfa paddock. The cows plunge in and start chomping on their favorite food. Tails swish contentedly, and the Indian brass bells around the cows' necks ring melodically. It sounds like a delicate Tulasi puja in the temple. The sky is blue, a refreshing breeze is blowing, and Krsna's cows are happy. What better form of devotional service can there be?

Hare Krsna Devi Dasi, an ISKCON devotee since 1978, spent several years on the Gita Nagari farm in Pennsylvania. She is co-editor of the newsletter Hare Krsna Rural Life.