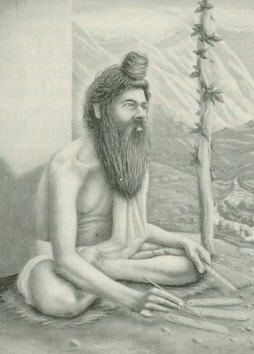

Srila Vyasadeva

SANDARBHA MEANS "essence" or "heart." Sad means "six." The Sad Sandarbhas are six treatises that give the essence of six topics about the Absolute Truth.

In the course of these six works, the author strongly establishes three points: (1) The Srimad-Bhagavatam is the highest source of knowledge. (2) Krsna in Vrndavana is svayam bhagavan, the original Personality of Godhead. (3) Prema, love of Krsna, is the supreme goal of life, beyond the happiness of impersonal realization and beyond all other forms of devotion.

Srila Jiva Gosvami upholds the first point in Sri Tattva Sandarbha, the second in the Krsna Sandarbha, and the third in the Priti Sandarbha.

The treatises of Srila Jiva Gosvami begin with the Tattva Sandarbha, or The Essence of Truth. Of the six this is the smallest, but that does not lessen its importance. For here Srila Jiva Gosvami lays the foundation for the philosophy of Krsna consciousness by setting forth its epistemology. He concludes that the Srimad-Bhagavatam is the highest scriptural authority for all human beings.

Sri Tattva Sandarbha has two sections. In the first Srila Jiva Gosvami tackles the question of pramana, or the valid means of acquiring knowledge not just any knowledge but transcendental knowledge, knowledge beyond the range of our senses and intellect. In the second section he defines the prameya, or object of knowledge.

He begins his task of writing the Sad Sandarbhas by quoting as an invocation a verse from Srimad-Bhagavatam (11.5.32):

krsna-varnam tvisakrsnam

sangopangastra-parsadam

yajnaih sankirtana-prayair

yajanti hi su-medhasah

"In the Age of Kali, intelligent persons perform congregational chanting to worship the incarnation of Godhead who constantly sings the names of Krsna. Although His complexion is not blackish, He is Krsna Himself. He is accompanied by His associates, servants, weapons, and confidential companions."

Through this verse, Jiva Gosvami indirectly tells us that Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu is his worshipable Deity and that he, Jiva, accepts the authority of Srimad-Bhagavatam as the ultimate.

Next Srila Jiva Gosvami explains why he is writing the Sandarbhas. He says that Sanatana Gosvami and Rupa Gosvami, his spiritual master, have directed him to write this book and so he is doing it as a service. He also expresses gratitude to Srila Gopala Bhatta Gosvami, whose notes and earlier attempt at writing the Sandarbhas form the basis of the present work.

Then Srila Jiva tells who he is writing for: "I write for those people whose only desire is to render service at the lotus feet of Lord Sri Krsna. Please do not show my book to anyone else. I curse the person who studies this book but does not desire to serve Krsna."

Alternatively, the last sentence may be read, "You [the reader] must vow not to show this book to anyone who does not desire to serve Lord Krsna."

Pramanas: The Valid Means Of Knowledge

To begin the book proper, Jiva Gosvami quotes a verse that sets forth the three basic divisions of spiritual life: knowledge of our relationship with the Supreme (sambandha); the process for realizing that knowledge (abhideya); and the ultimate goal of life (prayojana). He then asks, "Where do we get evidence about this?"

In reply he lists the ten kinds of pramana, or means of acquiring knowledge, customarily used in India's philosophical traditions. He reduces the ten to three, because these three contain the other seven. This was shown by the great scholar and devotee Srila Madhvacarya.

The three pramanas Jiva accepts are sense perception (pratyaksa), inference (anumana), and verbal testimony (sabda). Of these he promptly discards sense perception and inference as unreliable.

All human beings, he says, are subject to four defects: We all make mistakes, we all have imperfect senses, we are all subject to illusion, and we all have a cheating propensity. Our sense perception, therefore, is hardly a reliable means for gaining knowledge, and for knowledge of what exists beyond our senses it is entirely useless. Inference he disposes of as equally unreliable, because inferential reasoning rests on sense perception, which he has already shown wanting. In short, the same defects that directly plague sense perception indirectly plague inference.

In the end, Srila Jiva Gosvami accepts sabda pramana, or verbal testimony, as the most reliable means of gaining knowledge because it is the only method that can deliver knowledge free of all human frailty.

Verbal testimony is of two types. One kind we are familiar with, for we routinely depend on the testimony of experts such as doctors and authorities such as teachers. But none of these sources is flawless. None is exempt from the four human defects listed above.

Therefore the second type of verbal testimony, called apauruseya sabda, is the one he has in mind. Apauruseya sabda means verbal testimony that has no human origin; it is revealed knowledge coming to us as a gift of the Divine. Such superhuman knowledge has no taint of the four defects of human beings. Srila Jiva Gosvami suggests that since we have no other means for gaining knowledge of the transcendental sphere, sabda pramana is worthy of closer inspection.

Where is such flawless knowledge to be found? Srila Jiva affirms that the Vedas are the answer.

Originally the Vedas were not written by any man or group of men. They emanated from the Supreme Lord, who revealed them to Lord Brahma, the first created being, who then passed them down. Since they are a product neither of human sense perception nor of human reasoning, the Vedas are not subject to the four human defects. Srila Jiva Gosvami says that since the original message of the Vedas has not been changed, the Vedas are the best candidate for a source of perfect knowledge.

One may contest Jiva Gosvami's stand on sabda pramana. For example, one might try to put aside the divine origin of the Vedas as nice myth. No doubt a thinker of Jiva Gosvami's stature could have foreseen many objections to his stand and could have written a thick volume to refute them; but he didn't. Instead of dwelling long on such discussion, he simply asserts that for his means of knowledge he will strictly limit himself to apauruseya sabda pramana, or the evidence of transcendental sound. Then he gets on with his main purpose.

He is right. Without allowing for the validity of transcendental sound, the best we can do is infer, "There is transcendence. Something is there." Beyond that we can only speculate, and we would not be able to validate our speculations. Any such approach would surely lead to endless futile debate, as in fact it has in the Western philosophical tradition.

Srila Jiva Gosvami now goes on to explain that the Vedas are no longer available in their entirety. Originally there were some 1,130 branches to the Vedic tree of knowledge, but scholars at the time of Jiva's writing found only twenty branches still extant. Jiva Gosvami argues that from such a small representation we cannot be sure we understand the message of the Vedas. The subject matter is difficult; the language, Sanskrit, is difficult; the line of teachers who might have helped us has broken; and even the twenty branches left entail more volumes than we can sort through in a lifetime. According to tradition, also, study of the Vedas is not open to everyone but only to the priestly class. Thus Srila Jiva Gosvami concludes that the highly abstruse message of theVedas can no longer be understood from study of the Vedas themselves.

As an alternative he proposes to study the Puranas, which have the same origin and so are also apauruseya sabda but were meant for those who cannot understand or approach the Vedas.

So now he analyzes the Puranas. But he finds that each Purana asserts that its particular deity is supreme. The Siva Purana says Lord Siva is supreme, the Skanda Purana says that Skanda is supreme, the Devi Purana says Devi is supreme, and so on for eighteen Puranas. So what is the conclusion?

To ascertain this, Jiva Gosvami analyzes further. He finds that the eighteen Puranas have three divisions: six are in the mode of ignorance, six in passion, and six in goodness. He says that we should focus our attention on the six in the mode of goodness because, as Krsna states in the Bhagavad-gita, ignorance leads to sleep, passion to greed, and goodness to knowledge.

But from the six Puranas in goodness, still there is confusion as to whether Lord Rama or Lord Nrsimhadeva or Lord Visnu or Lord Krsna is supreme. Here Jiva Gosvami takes a different tack. He says, "If we can find a book which explains Vedanta, which explains the Gayatri mantra, which is apauruseya, which is completely available, and for which a disciplic line exists, then we should analyze that book."

He finds that the book which best fits these criteria is the Bhagavata Purana, or Srimad-Bhagavatam, and so he will analyze the Srimad-Bhagavatam. The Sad Sandarbhas are nothing but an in-depth analysis of the Bhagavatam.

Srila Jiva Gosvami now establishes that the Srimad-Bhagavatam is the natural commentary on the Vedanta-sutra. The Bhagavatam is completely available in eighteen thousand verses, it begins with the Gayatri mantra, and there is a disciplic line for it as well. And great scholars in the past, such as Adi-sankara, Madhvacarya, and Ramanujacarya, held the Bhagavatam in high regard. From all this he concludes that of the six Puranas in the mode of goodness Srimad-Bhagavatam is the ultimate sabda pramana and therefore worthy of detailed analysis.

Jiva Gosvami says, therefore, that although he will quote other sources, he will quote Bhagavatam as the highest authority, not to reinforce his words but to establish the meanings from the Bhagavatam that he wishes to explain. He mentions that he will quote Sridhara Svami's commentary, Bhavartha Dipika.

Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu accepted Sridhara Svami's commentary. Jiva Gosvami, therefore, in accord with Lord Caitanya's wishes, will quote from Sridhara Svami's words whenever possible. Jiva notes, however, that in some places Sridhara Svami did not speak clearly enough. So in those places, Jiva says, he will make his own comment.

Again, some of Sridhara Svami's comments are not strictly in line with the bhakti principles, because Sridhara Svami was using the logic called badi-samisa nyaya, which means that if you want to catch fish you have to feed them meat. Your goal is not to feed the fish but to catch them. Similarly, Sridhara Svami didn't want the impersonalists to reject him out of hand, so he wrote a mixed commentary, though he made clear from the outset that he accepts the personal feature of the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

Jiva Gosvami has been criticized in contemporary academic circles for using Sridhara Svami for his own purpose and not really respecting his authority. But Jiva makes no secret of his motives. He makes clear that in his system of authority Sridhara Svami plays only a supporting role.

Srila Jiva Gosvami ends the first section of the Tattva Sandarbha by pointing out that Madhvacarya wrote a commentary on the Bhagavatam and that although Sri Ramanuja did not, the Bhagavatam is an often quoted reference in his works. There can be no question, therefore, that these great philosopher saints accepted the Bhagavata Purana as authoritative.

Prameya: The Knowable

Jiva Gosvami next declares that he will analyze the heart of Sukadeva Gosvami, the speaker of the Bhagavatam, through a verse by Suta Gosvami. In that prayer, Suta says, "I bow to Sukadeva Gosvami, the destroyer of all sins, the son of Vyasa. His mind was filled with the bliss of impersonal realization, and he was devoid of all worldly thoughts, yet His heart was drawn to the enchanting pastimes of Ajita [Krsna]. Sukadeva Gosvami has compassionately revealed this Purana, which revolves around the Supreme Personality of Godhead. My salutations unto Sukadeva Gosvami."

Suta mentions that Sukadeva was absorbed in impersonal realization. This means that Sukadeva had no material desires. Srimad-Bhagavatam, therefore, must not be mundane, because Sukadeva had already gone beyond interest in anything mundane. Furthermore, the knowledge in Srimad-Bhagavatam must surpass the happiness of impersonal realization. What Sukadeva spoke to Pariksit Maharaja could not have been impersonalism, because Sukadeva had already rejected that along with materialism.

Having analyzed the heart of the speaker, Jiva Gosvami now wants to analyze the heart of the writer, Vyasadeva. Srila Jiva wants to elicit our agreement that the writer and the speaker are of one mind. His study of Vyasa proceeds from the Bhagavatamverses in the second chapter that state, "By bhakti-yoga he saw the Purna Purusa, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, along with His potencies and all His associates. Vyasa also saw the living entities bewildered by Maya…." Vyasadeva concludes that simply by listening to the Bhagavatam one is freed from the clutches of illusion and attains devotion to Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

After writing the Bhagavatam, Vyasa taught it to Sukadeva Gosvami. Why Sukadeva, who wore not even a loincloth? Why not one of many other disciples? He taught Sukadeva, Jiva says, because Sukadeva was completely nivrtta (detached from material life) and had no scope at all for misusing this highest knowledge.

The section of the Bhagavatam Srila Jiva Gosvami is quoting here shows the heart of Vyasadeva and the heart of the Krsna conscious philosophy. This passage directly mentions bhakti and Krsna and the energies of the Lord. No one, therefore, can accuse Jiva of juggling words or merely putting forward the partisan views of his school. Rather, he goes deep into the original message of the author himself and mines it for all its worth. Srila Jiva originally called his work the Bhagavata Sandarbha, or the essence of the Bhagavata Purana, for he reveals the heart of the Bhagavatam.

Srila Jiva Gosvami next analyzes the heart of Suta Gosvami, again with a similar format: he takes verses spoken by Suta in the second and third chapters and analyzes them to arrive at the same conclusion of bhakti. Srila Jiva Gosvami says we can go on analyzing this way for all the principal speakers Maitreya Muni, Narada Muni, and others. If we do so, he says, we will see beyond a doubt that the whole purpose of Srimad-Bhagavatam is to explain three things: sambandha, abhideya, and prayojana.

The first four Sandarbhas, therefore, deal with sambandha, the fifth deals with abhideya, and the sixth with prayojana. The sambandha portion takes four books because on this one aspect there is rampant confusion and there are many conflicting philosophies. Srila Jiva considers this topic, therefore, in minute detail.

Satya Narayana Dasa was born in a family of devotees in a village between Vrndavana and Delhi. He holds a postgraduate degree in engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology. While working in the U. S. as a computer software consultant, he joined ISKCON in 1981. He later received spiritual initiation from ISKCON leader Bhakti-svarupa Damodara Swami. He now teaches Sanskrit at the Bhaktivedanta Swami International Gurukula in Vrndavana and is translating the Sad Sandarbhas.

Kundali Dasa joined ISKCON in 1973 in New York City. He has taught Krsna consciousness in the United States, India, the Middle East, and eastern and western Europe. He has written many articles for Back to Godhead and is now editing Satya Narayana Dasa's translation of the Sad Sandarbhas.