Despite being a layman in the matter of law, I would like to step forward and apply a few commonsense legal rules of thumb to one of this century's most fiercely debated issues: abortion.

Even most proabortionists would agree that, biologically speaking, life begins at conception, when the sperm mixes with the ovum in one of the fallopian tubes. But the abortion debate hinges on the question not of when life begins but of when human life begins. When does the fertilized egg, fetus, or child in the womb become a human being, a person entitled to full protection under the law?

There is little consensus on the answer to this essential question. Scientists, philosophers, and theologians show up on both sides of the debate, some claiming that human life begins at conception, others asserting that it doesn't begin until birth, or even later. Various medical authorities have designated each stage of pregnancy between conception and birth as the beginning of human life. Implantation, when the fertilized egg becomes embedded in the wall of the uterus (about a week after conception); the start of a regular fetal heartbeat (about thirty days after conception); the point at which brainwaves appear on an electroencephalograph (about forty-five days); and viability, the stage at which the fetus can survive outside the womb all are likely candidates for the start of human life.

Faced with this broad range of conflicting opinions, the U.S. Supreme Court admitted in the 1973 case of Roe v. Wade that it was unable "to resolve the difficult question of when [human] life begins." The Court confirmed that if the fetus were indeed a person, his right to life would have to be guaranteed. But who was to answer the crucial question? Justice Blackmun, author of the majority opinion, wrote: "When those trained in the respective disciplines of medicine, philosophy, and theology are unable to arrive at any consensus, the judiciary, at this point in the development of man's knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer."

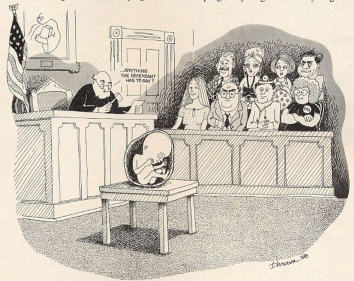

At this point the lawyer in me begins to stir. Justice Blackmun's statement clearly acknowledges that the fetus might be a person. It would seem to follow that we shouldn't risk destroying it until we find out for sure. Every Perry Mason fan knows that a defendant is innocent until proven guilty "beyond a reasonable doubt." This protects the defendant from unjust punishment, especially if his life is at stake. Although we are not trying to decide whether the fetus is innocent or guilty but whether it is human or not, the same principle applies: to protect the fetal "defendant" we have to assume he's a person. If we go ahead and allow abortion, we risk being guilty, as the prolifers say, of murder.

Anyone at all familiar with the abortion issue knows, however, that Roe v. Wade was the landmark decision that overturned all existing abortion laws and cleared the way for mass abortions. Even though the Court had indirectly admitted that the fetus might be a person, the decision made abortion legal from the day of conception right up to the day of birth. In a concession to antiabortion forces, the Court allowed the states to forbid abortion after the sixth month of pregnancy unless pregnancy threatens the woman's health. The Court failed to define "health," however, thus leaving a gaping loophole in would-be state restrictions. According to the World Health Organization, health is "a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, not simply the absence of illness and disease." On the basis of this or other broad definitions, any woman, with the assistance of an obliging doctor, could have her pregnancy diagnosed at any stage as a threat to her health.

The Roe v. Wade decision was so contradictory that even some leaders of the proabortion movement were a little dismayed. Why hadn't the Court gone ahead and defined human life as beginning at birth? Instead, it had admitted that human life might begin in the womb and then legalized abortion anyway. The liberalization of abortion laws was welcome, but the logical grounds for the Court's decision were flimsy at best.

On the other side, leaders of the anti-abortion movement, outraged by the decision, sought to nullify it by introducing a constitutional amendment called the Helms-Hyde bill. This bill attempted to answer the question the Court had so carefully skirted: "For the purpose of enforcing the obligation of the states under the fourteenth Amendment not to deprive persons of life without due process of law, human life shall be deemed to exist from conception." The bill was defeated in Congress, and Roe v. Wade remains the standard for abortion up to the present day.

But critics, President Reagan among them, continue to underline the decision's basic flaw. In a 1981 press conference Reagan said: "Until we make to the best of our ability a determination of when life begins, we've been opting on the basis that 'Well, let's consider they're not alive.' I think that everything in our society calls for opting that they might be alive."

From the Vedic viewpoint, the Court's decision in Roe v. Wade, while untenable, was not surprising. The Srimad-Bhagavatam, the topmost Vedic literature, explains that when a society considers sensual enjoyment the goal of life, the result is bound to be madness. According to the Bhagavatam, the desire for unrestricted sensual pleasure drives materialistic societies to perform activities that defy even common sense and betray a collective mentality more base than that of the dogs and pigs. To attain the goal of sensual pleasure, a materialisitic society can sacrifice everything else, including life itself.

Modern materialistic societies have invested virtually all their time and energy in the pursuit of sensual pleasure, especially sex, and the unborn child is a most serious threat to that investment. Justice Blackmun put it like this: "Maternity, or additional offspring, may force upon a woman a distressful life in the future. Psychological harm may be imminent. Mental and physical health may be taxed by child care. There is also the distress, for all concerned, associated with the unwanted child, and there is the problem of bringing the child into a family already unable, psychologically and otherwise, to care for it."

Justice Blackmun would have been more direct if he'd said that the child in the womb interferes with a carefree life of sexual intercourse without responsibility and consequences. Pregnancy is long and troublesome; birth is usually painful and expensive. The newborn child requires constant care and attention and creates a financial burden for the parents or for the government that may last for twenty years or more. And more often than not the unborn child is a social embarrassment as well: seventy-five percent of the women who have abortions are unmarried; sixty-six percent are between fifteen and twenty-four years old.

Faced with this threat to its considerable investment in sexual enjoyment, a materialistic society arranges to eliminate the child before he leaves the womb. When a society is caught in the passionate grip of sexual attraction, its decision to sanction abortion doesn't rest ultimately on philosophical, theological, or scientific considerations. No, abortion is just plain good business. In a society suffering from madness, even the highest judicial body may either ignore the fact that abortion could be murder, or just not care.

Here again it doesn't take a lawyer to expose a flagrant violation of a very basic principle of justice. From merely reading the morning papers, one can learn to what lengths the American judiciary will go to select an unprejudiced jury. This is especially true when the defendant is both well known and disliked. John W. Hinckley, for example, was so infamous that the court had to devote an extraordinary amount of time to finding impartial jurors. Many attorneys believe trials are frequently won or lost during jury selection.

And yet, in the trial of perhaps the best known and most disliked defendant of all the unwanted fetus no one has tried to find an impartial jury. Why has the fetal defendant been judged nonhuman despite strong evidence to the contrary? Because the "jury" in this case, a society insanely addicted to sex is strongly biased against him. It has everything to gain by judging the child nonhuman, everything to lose if he's judged human.

To set the abortion issue straight, therefore, we need to select an impartial jury a group of men and women to whom the unborn child is not a threat. The jurors must be persons who have the highest reverence for human life, who feel that although the mother's physical and mental health may be strained by bearing and raising offspring, these hardships alone are no justification for destroying the child in the womb. In other words, an impartial jury must consist of men and women who, understanding that the highest goal of human life is self-realization, have permanently set aside the maddening, piggish life of sense enjoyment.